To Caesar You Shall Go!

READ PREVIOUS

(PART 7)

GO TO SERIES

Paul’s visit to Jerusalem to celebrate the Feast of Pentecost and to deliver relief aid collected by the churches in the Diaspora seemed to go well at the outset (Acts 21:17–20; see also Acts 20:16; 24:17; Romans 15:25–31).

However, aware of the potential for local opposition to the “apostle to the gentiles,” James and the elders advised him to participate in a seven-day ritual at the temple with four other Jewish followers of Jesus, who had taken a vow to purify themselves before God. They also asked Paul to show generosity by paying their associated expenses. This, they said, would offset the rumor among some of the Jewish church members that Paul was not law-observant and that he taught Diaspora Jews to disregard Moses’ teaching in respect of infant male circumcision and of following the traditions. They added that the letter they had previously sent to gentile believers about four physical requirements for entry into the spiritual community of Israel still held—though by implication, the need for adult male circumcision was rescinded (Acts 21:25; see also Acts 15).

“It will become obvious to everyone that there is nothing to the rumors going around about you and that you are in fact scrupulous in your reverence for the laws of Moses.”

Paul complied with the elders’ request, but just before his week of purification was ended, he was accosted in the temple—not by fellow believers but by some nonbelieving Jews from Asia, no doubt also in Jerusalem for the Feast of Pentecost. His attackers, probably from Ephesus, pointed him out as “the man who is teaching everyone everywhere against the people and the law and this place” (Acts 21:28). They further accused him of defiling the temple by bringing gentiles into the part reserved for Jewish worshipers. It was a false accusation, as they had merely seen him in the city with one of his companions, Trophimus, a gentile from Ephesus.

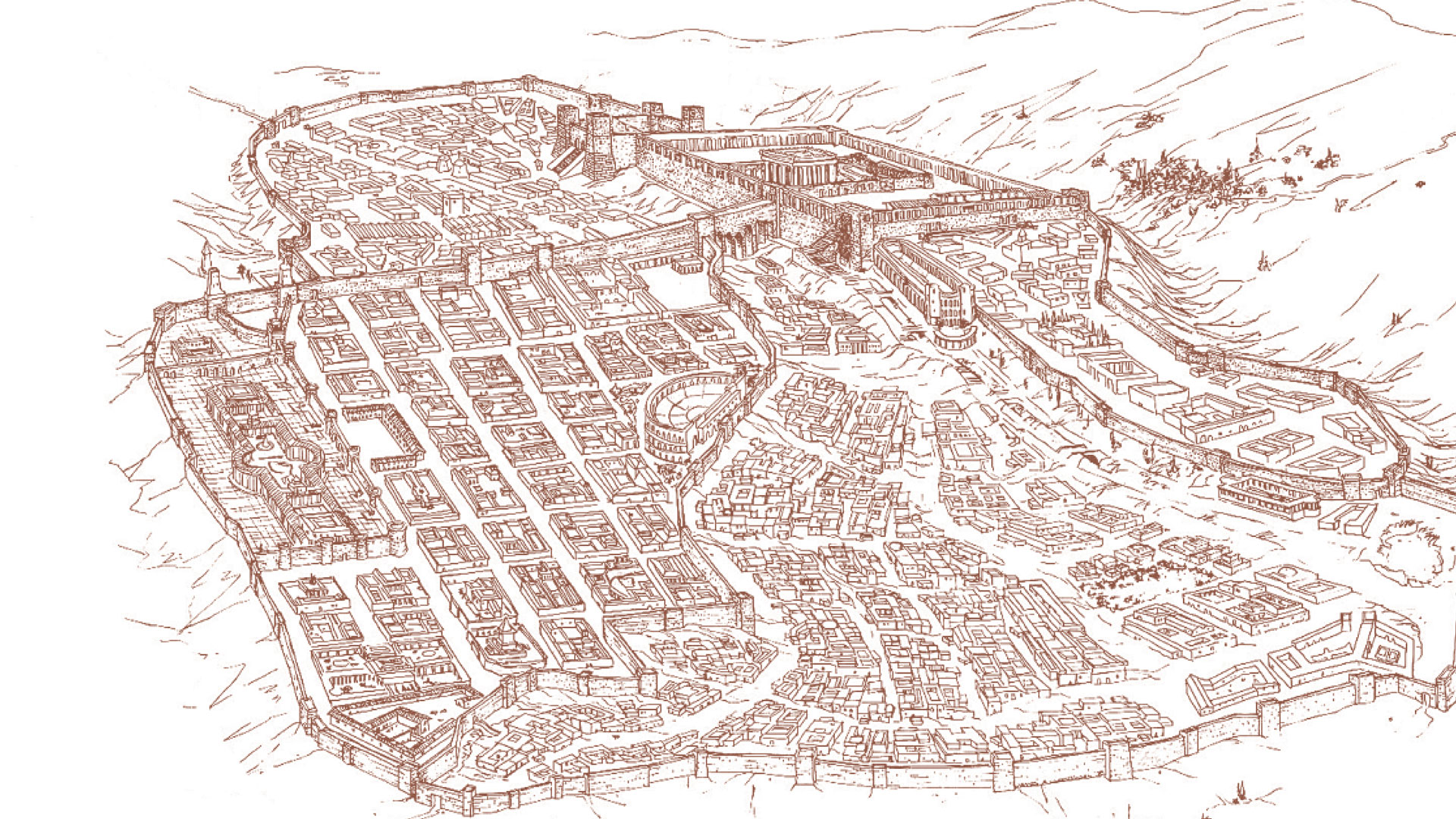

The ensuing riot brought the Roman garrison guard of soldiers and centurions, as well as Claudius Lysias, their commander or tribune, to the scene. Their arrival stopped Paul’s beating at the hands of the mob that had by now dragged him into the Court of the Gentiles, the temple gates being closed to prevent Paul gaining sanctuary and to make sure the sacred area wouldn’t be defiled by murder.

The tribune arrested and chained Paul and tried to ascertain what had happened, but the crowd was so wild and noisy that it was impossible to get the story straight. Paul was escorted to the barracks, probably in the adjacent Antonia fortress, and carried up the steps by the soldiers for his own protection from the crowd still shouting out for his death. On the steps, he asked Claudius Lysias, in Greek, if he could address the crowd. The tribune agreed, surprised that the prisoner could speak the language: he had assumed that Paul was the wanted Egyptian leader of 4,000 terrorists or sicarii (assassins). This same Egyptian is mentioned by the Jewish historian Josephus as being active during the rule of Felix, the Roman procurator of Palestine (52–60 C.E.), before whom Paul would soon appear. Paul answered the tribune that, to the contrary, he was a Jewish citizen of Tarsus in Cilicia, well known as a Hellenic educational center (verses 37–39).

Deft Defense

With permission to speak, Paul motioned with his hand and the crowd quieted. What follows is another example of his ability to communicate with an audience effectively and economically. Having spoken to great effect in Greek to the commander moments earlier, he now turned to the murderous mob and addressed them politely in a Hebrew dialect, Aramaic. He began in a way designed to elicit their attention: “Brothers and fathers [or “My elders and my companions”], listen while I explain why I am not guilty” (Acts 22:1, paraphrased). Luke’s account says that “when they heard that he was addressing them in the Hebrew language, they became even more quiet” (verse 2).

Paul then told his story, crafted in such a way as to keep his audience attentive. He gave them reason to identify with him further, relating that he was an Israelite, born in the Diaspora city of Tarsus, but educated in Jerusalem by a famous teacher, Gamaliel, in the Pharisaic school of thought. He was zealous for God “as all of you are this day.” In effect, “I am just like you.” He related how he had persecuted the followers of Jesus as a sect (“this Way”) to the death, the high priest and the council of Jewish leaders, the Sanhedrin, being his witnesses: it was from them that he had gained approval to go to Damascus to take Jesus’ disciples captive and bring them to Jerusalem for punishment. In other words, “I was as opposed to the sect as you now are to me.”

Then, making the turn in his argument, he began to give account of his change of heart. He explained what had happened to him on the road to Damascus, how he had been temporarily blinded and how he had become a follower of the Way. He showed how a devout and well-respected Jew had been God’s intermediary to restore his sight and had delivered a message from Him. He explained that it was even in the temple, as he prayed, that Jesus had revealed to him in vision that he was to leave Jerusalem, where his message would be opposed. Paul then showed how he had argued that the Jerusalemites would surely listen because he had participated in the persecution of Jesus’ followers, including the martyr Stephen (see Acts 7:57–8:3). But Jesus had told him, “Go, for I will send you far away to the Gentiles” (Acts 22:21).

It was the word Gentiles that ended Paul’s speech. Despite all of his rhetorical skill, the crowd was now on fire again. It was all they had to hear to erupt into another riot and demand his death.

At this, the tribune took Paul inside the barracks to “examine” him by flogging, in the hope of finding out why he was the cause of such uproar. He had likely not understood the prisoner’s defense, given in Aramaic. All he could see was the result.

At the prospect of severe punishment, Paul’s presence of mind helped him once more, as it had in Philippi. As the soldiers stretched him out for the whipping, he asked a centurion whether it was lawful to flog an uncondemned Roman citizen. Of course it was not, and Paul knew it. When the tribune learned of Paul’s question, he came immediately and questioned him about his citizenship, admitting that his own had been purchased. Paul replied that he was Roman by birth—a superior form of citizenship. Now the soldiers and their leader were afraid. The next day, Claudius Lysias had Paul freed from his chains and brought him together with the chief priests and the Sanhedrin to ask more about the reasons for the riot (verses 25–30).

Paul’s opening remarks were similar to those made to the crowd. Addressing them as “brothers,” he said that he had always lived in good conscience before God. At that, Ananias, the high priest (47–58 C.E.), told those next to him to hit him in the mouth. Paul’s anger flared: “God is going to strike you, you whitewashed wall!” He was incensed at such hypocrisy and injustice coming from one who as a judge was ignoring the very law he was representing. This caused further alienation for Paul, who had not realized that he was addressing the high priest himself. He quickly apologized, knowing that the Scriptures said, “You shall not speak evil of a ruler of your people” (Acts 23:1–5).

But how was Paul to get back control of the situation with his opponents? Knowing that some were Sadducees and some were Pharisees, he exploited a crucial difference in their beliefs and spoke the truth at the same time. The Sadducees did not accept the existence of angels or spirits or that the dead will be resurrected. Paul said loudly, “Brothers, I am a Pharisee, a son of Pharisees. It is with respect to the hope and the resurrection of the dead that I am on trial” (verse 6). This brought the meeting to an impasse, with each side noisily arguing its perspective, some of the Pharisees now protesting strongly and supporting Paul: “We find nothing wrong in this man. What if a spirit or an angel spoke to him?” (verse 9). When the situation turned violent and Paul’s life was again in danger from the contending parties, the tribune intervened and had him taken back to the barracks.

“The following night the Lord stood by [Paul] and said, ‘Take courage, for as you have testified to the facts about me in Jerusalem, so you must testify also in Rome.’”

That night Paul was encouraged by Jesus, who appeared before him and told him, “As you have testified to the facts about me in Jerusalem, so you must testify also in Rome” (verse 11).

On to Felix

The next day more than 40 Jews conspired together to kill Paul and bound themselves by an oath not to eat or drink until they had succeeded. That’s to say, the threat was immediate. The 40 zealots went to the elders and priests and told them to ask the tribune to send the prisoner to them for further questioning, whereupon the conspirators would kill him. But Paul’s nephew heard of the plot and informed his uncle. Paul called one of the officers, who took the young man to Claudius Lysias. Once the tribune understood what was about to take place, he told the nephew to say nothing more about it, and he arranged for Paul to have a couple of horses and an escort of 470 soldiers to accompany him by night to the coastal fortress of Caesarea. There he would be judged by Felix the governor, who, according to the letter the tribune wrote, should hear the council’s case against the Roman citizen once more, even though Claudius Lysias had found nothing worthy of death in Paul’s behavior (verses 12–30).

On arrival, Felix asked Paul where he was from and, hearing that it was Cilicia, put him in the palace built by Herod the Great until his accusers should come.

Presenting legal cases to Roman authorities demanded certain skills, and the Jewish leaders decided that their best chance for success was to use a professional orator and lawyer named Tertullus. When he arrived five days later with Ananias and some of his elders, he was primed: “Since through you we enjoy much peace, and since by your foresight, most excellent Felix, reforms are being made for this nation, in every way and everywhere we accept this with all gratitude” (Acts 24:1–3). His generous opening soon gave way to three religiously based accusations, supported by the Jews. Paul, he said, was a dangerous nuisance, a man who started riots among the Jews everywhere and a leader of a religious party, or sect, identified as the Nazarenes. His hope was that Felix would see Paul as a political nuisance, a threat to public order.

The governor motioned for Paul to speak. The apostle also began with a compliment to Felix, mentioning his long years of service as a judge to the nation. Paul welcomed his knowledgeable oversight. Inviting the governor to ascertain that it was only 12 days since he had gone up to Jerusalem, he said that even during that short time there had been no evidence of his causing problems in synagogues or the temple. The accusations were false and his opponents had no proof.

Paul was willing to admit one thing, however—that he was a follower of “the Way” that his detractors had derogatorily called a sect. The Way, he said, was consistent with the law and the prophets. Further, he said his enemies believed in the resurrection as he did. His visit to Jerusalem was to bring a charitable gift to his nation and to present offerings at the temple. As he was doing so, Ephesian Jews had wrongfully accused him and started a riot. And as his present accusers well knew, he was now standing before Felix only because he had called out among them, “It is with respect to the resurrection of the dead that I am on trial before you this day” (verses 14–21).

Felix, whom Luke tells us had “a rather accurate knowledge of the Way” (his wife Drusilla was Jewish), put off the hearing, saying that he wanted Claudius Lysias to attend a future meeting before making a decision. Paul was allowed to remain under relatively open house arrest, with his friends able to visit and help him.

Another Governor, Another Hearing

After a few days, Felix sent for Paul and listened as he explained about having faith in Jesus Christ. The governor became frightened when Paul talked further about “righteousness and self-control and the coming judgment” (verse 25), telling him that he would talk to him again later. Luke notes that Felix was hoping for a bribe and so kept sending for him. This went on for two years until Felix was replaced by Porcius Festus. But because Felix wanted to do the Jews a parting favor, he left Paul in prison.

When Festus had been in the province just three days, he went up to Jerusalem from Caesarea. Ever eager to get rid of Paul, the religious leaders urged the new governor to send him back to Jerusalem, planning to ambush and kill him on the way. Festus would only agree to try the case in the provincial capital and asked that the Jewish leaders send a delegation there. After about 10 days he went back to Caesarea and the next day asked that Paul be brought before him, the Jerusalem leaders being present. As before, accusations flew, but the argument seemed to Festus to be about matters of the Jewish religion and someone called Jesus, who had died (yet whom Paul said was alive), rather than a serious crime (Acts 25:1–7; see also verses 18–19).

“If the charges brought against me by these Jews are not true, no one has the right to hand me over to them. I appeal to Caesar!”

Paul argued in his own defense, “Neither against the law of the Jews, nor against the temple, nor against Caesar have I committed any offense” (verse 8). In an attempt to please the religious leaders, Festus asked Paul if he would go back to Jerusalem to be tried before him. Now Paul replied more forcefully. Pleasing the Jews was insufficient reason to try him in Jerusalem. Since he had done nothing against the law, the temple or the emperor, he exercised his right of appeal as a Roman citizen to stand before Caesar himself and be heard. Festus first consulted with his advisors, then granted Paul’s request: “To Caesar you have appealed; to Caesar you shall go” (verse 12). Yet Festus knew that he did not have enough information on the nature of the charge against Paul to send him immediately to Rome (see verse 27).

After some time, the local king, Herod Agrippa II, arrived in Caesarea with his sister Bernice to pay respects to the new governor. Though Agrippa ruled a small area north of Palestine, he had the authority to appoint the Jewish chief priest. Festus took the opportunity to mention Paul to Agrippa, hoping perhaps for some guidance in what he might tell Caesar about the prisoner. The next day Paul had his audience with the king. Agrippa, Bernice and their entourage entered Herod’s palace with great pomp. High-ranking military men and city fathers were there as Paul was brought in. In explaining the prisoner’s situation, Festus recapped his previous judgment: “I found that he had done nothing deserving death” (verse 25). Agrippa then said to Paul, “You have permission to speak for yourself.”

Next time in The Apostles, Paul’s final defense in Palestine and his journey to Caesar’s Rome.

READ NEXT

(PART 9)