Lamenting the Fallen City

In the aftermath of the Babylonian siege and destruction of Jerusalem in the sixth century BCE, a Hebrew poet expresses his nation’s despair over a broken relationship with its God, as well as the hope of reconciliation.

READ PREVIOUS

(PART 29)

GO TO SERIES

The siege and capture of Jerusalem under the Babylonian invasion of Nebuchadnezzar (588–586 BCE) was the worst experience the city had endured. It’s memorialized in a series of five dirges, or funeral poems, known collectively as “Lamentations” or “The Lamentations of Jeremiah.” Even though the book does not name any author, the Septuagint version of the Hebrew Scriptures states (following Jewish tradition): “And it came to pass, after Israel was taken captive, and Jerusalem made desolate, that Jeremiah sat weeping, and lamented with this lamentation over Jerusalem, and said . . .”

In the Hebrew canon, Lamentations is placed third in the scroll of five short books read at annual festivals and observances—in this case the fast of the 9th of Av. On that date each year, Jews commemorate not only the temple’s destruction by the Babylonians in 586 BCE and by the Romans in 70 CE, but other catastrophic episodes in Jewish history, among them the day Bar Kokhba’s last fortress fell to Hadrian’s forces in 135 CE; the date in 1290 when Edward I signed an edict banishing Jews from England; and the time of the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. No wonder, then, that according to one modern rabbinic authority, Lamentations is “the eternal lament for all Jewish catastrophes, past, present, and future.”

The first four of the book’s five chapters follow an acrostic pattern, where each of the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, aleph through tav (in sequence), begins a verse. The book thus opens with aleph, the first letter in the word ekah (“alas,” “how”)—its title in the Tanakh. This opening is repeated in chapters 1, 2 and 4. Chapter 3, the center of book, has 66 verses that follow the Hebrew alphabetical order in 22 sets of three verses each. Though chapter 5 is not an acrostic, it does contain 22 lines. This precise literary structure contributes to the feeling of formal mourning for the ruined city and for the people who have died or been taken captive to Babylonia.

“The book of Lamentations is unique among the poetic books of the Old Testament: it is the only book which is entirely in poetic form.”

Though the book is anonymous, several passages parallel Jeremiah’s historical and prophetic writings about Judah’s collapse because of unfaithfulness to God. The book also reflects the prophetic curses for disobedience recorded by Moses in Deuteronomy 28. Nonetheless, hope of renewal and restoration is expressed in chapters 3 and 5.

The book of Lamentations is obviously focused on the siege and destruction of Jerusalem and the captivity of Judah by the Babylonians, yet it lends itself to a much broader application. It is, in effect, a microcosm of humanity’s broken relationship with the Creator and how it can be restored.

The Ruined City

The first chapter divides into two equal sections, viewing Jerusalem’s destruction and Judah’s captivity from an observer’s perspective (verses 1–11) and then from the city’s vantage point (verses 12–22).

So in the first verse we read, “How lonely sits the city, that was full of people! How like a widow is she, who was great among the nations! The princess among the provinces has become a slave!” The widowed city responds, “Is it nothing to you, all you who pass by? Behold and see if there is any sorrow like my sorrow, which has been brought on me, which the Lord has inflicted in the day of His fierce anger” (verse 12).

And in verse 2: “She weeps bitterly in the night, her tears are on her cheeks; among all her lovers she has none to comfort her. All her friends have dealt treacherously with her; they have become her enemies.” This is about the loss of allies and friends because of betrayal—the price Judah paid for failing to rely on God. The thought is echoed in verse 19 in the personified city’s own remarks: “I called for my lovers, but they deceived me; my priests and my elders breathed their last in the city, while they sought food to restore their life.”

In the attack on Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar, they had in fact turned to the Egyptians for help rather than to God. The nation’s misguided reliance on outside help eventually brought Jerusalem/Judah to ruin, unable to be comforted. Jeremiah had earlier prophesied this outcome, recording God’s words as a warning to them: “All your lovers have forgotten you; they do not seek you; for I have wounded you with the wound of an enemy, with the chastisement of a cruel one, for the multitude of your iniquities, because your sins have increased” (Jeremiah 30:14). What happened was therefore predictable.

In verses 13–22 of Lamentations 1, the personified Jerusalem alternates between self-pity and repentance, between accusation toward God and acknowledgment of rebellion against Him, begging for His intervention to punish the invaders.

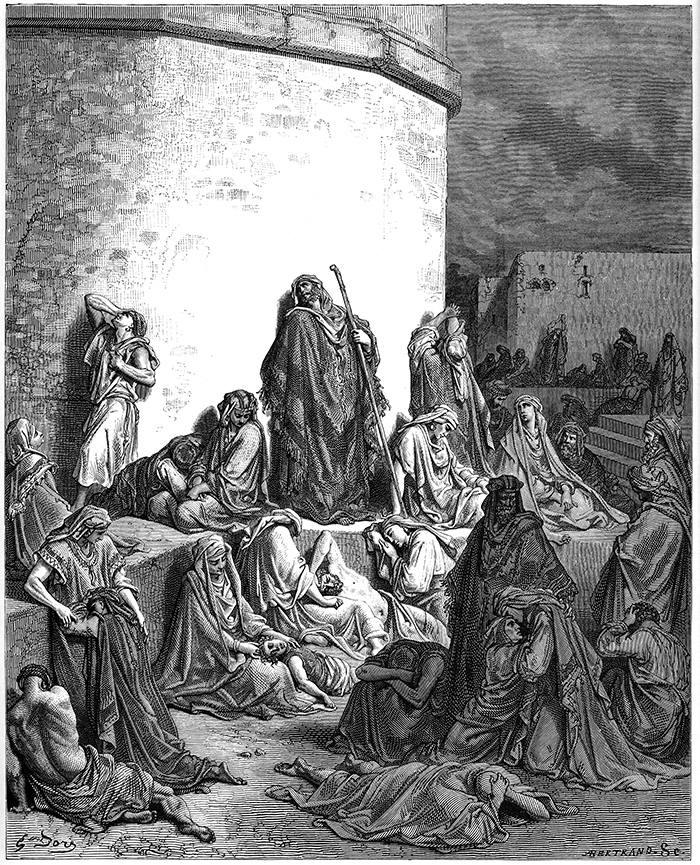

The People Mourning Over the Ruins of Jerusalem by Gustave Doré, engraving (1866)

The second chapter is an intensification and expansion of chapter 1 and adds a third voice: a third-person narrator speaks in verses 1–10; someone else speaks in the first person, first about the city (11–12) and then to the city (13–19); then Jerusalem speaks in verses 20–22.

Lamentations 2 details God’s anger against Jerusalem and Judah, the people’s suffering from food shortages, the destruction of towns and villages, and the loss of temple, of religious ceremonies, of priest and king, and of the Law. Some commentators identify the voice of Jeremiah very clearly in this chapter, as well as in chapter 1, because of similar ideas expressed in several chapters of Jeremiah.

The author seeks to comfort the ruined city because her prophets have failed her through false teaching and delusion. Enemies have mocked her downfall. Though they call on God for help in the face of famine—with mothers reduced to eating their own children—and the slaying of the nation’s young men and women, their sins have cut them off so that He will not hear.

From Suffering to Hope

The third chapter, with its lengthier acrostic, is the heart of the book. It helps explain our earlier observation that the book could be viewed as a microcosm of humanity’s relationship with God.

The first section deals with unremitting personal suffering inflicted by God because of unremitting sin. This is humanity’s story from the beginning. Genesis records what happened to the pre-Flood world because of such sin. It isn’t that God prefers punishment or delights in it; but being faithful to His word, it is the necessary outcome of sin. He is as faithful about the penalty for sin as He is faithful about His blessings.

“Lamentations . . . aids a proper understanding of why the exile occurred and how one may turn to the Lord in the aftermath and ensuing years of the exile.”

The chapter is written from the perspective of a tormented and perplexed participant in Jerusalem’s destruction: “I am the man who has seen affliction by the rod of His wrath. He has led me and made me walk in darkness and not in light. Surely He has turned His hand against me time and time again throughout the day” (3:1–3).

But this chapter eventually brings hope back into the picture: “Through the Lord’s mercies we are not consumed, because His compassions fail not. They are new every morning; great is Your faithfulness. ‘The Lord is my portion,’ says my soul, ‘therefore I hope in Him!’” (verses 22–24).

Patience in waiting on God is recognized as an essential in times of affliction: “For the Lord will not cast off forever. Though He causes grief, yet He will show compassion according to the multitude of His mercies. For He does not afflict willingly, nor grieve the children of men.” This leads to reflection on the need to consider how sin cuts off all people from God and why punishment is part of the way back. Under these conditions, God will hear and save the repentant from their enemies (verses 25–27; 31–33; 40–42; 55–60).

Chapter 4 returns to detailing the suffering of the city and its inhabitants during the siege. Especially harrowing is the fate of young children: “The tongue of the infant clings to the roof of its mouth for thirst; the young children ask for bread, but no one breaks it for them. . . . The hands of the compassionate women have cooked their own children; they became food for them in the destruction of the daughter of my people” (4:4, 10).

Some of Jerusalem’s attackers are warned that they, too, will suffer. The nation of Edom, for example, would be repaid for their involvement in Judah’s downfall: “Rejoice and be glad, O daughter of Edom, you who dwell in the land of Uz! The cup shall also pass over to you and you shall become drunk and make yourself naked. . . . He will punish your iniquity, O daughter of Edom; He will uncover your sins!” (verses 21–22).

Looking to the Future

The fifth and final dirge is not an acrostic and reads quite differently from the other chapters. The sense is that the book is winding down, coming to a close. It is, in effect, a prayer that restoration will come to Judah.

“The prayer of Lamentations 5:21–22 was not a doubting cry from a discouraged remnant. Rather it was the response of faith from those captives who had mastered the lessons of Deuteronomy 28 and the Book of Lamentations.”

Recapping the price paid for sin in terms of loss of land, captivity, foreign oppression, food insecurity, rape, torture and forced labor—again, the kind of curses laid out in Deuteronomy—the penitent’s prayer concludes with hope for recovery: “You, O Lord, remain forever; Your throne from generation to generation. Why do You forget us forever, and forsake us for so long a time? Turn us back to You, O Lord, and we will be restored; renew our days as of old, unless [better translated “even though”] You have utterly rejected us, and are very angry with us!” (verses 19–22).

As suggested earlier, the book of Lamentations echoes the human story and is therefore both historic and future-facing. It is the story of humanity from the beginning, detailing what happens when sin prevails among a people. But there is hope, because God is merciful and ready to forgive and restore.

READ NEXT

(PART 31)