With the Promised Land in View

READ PREVIOUS

(PART 10)

GO TO SERIES

Forty years had passed since the children of Israel exited Egypt as a great multitude of freed slaves. The faithlessness of many during their wilderness journey across the Sinai resulted in the failure of most adults in the exodus generation to enter the Promised Land.

The final book of the Law, or Torah, is known in English as Deuteronomy. It acts as a bridge between the first four books of Moses and the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings), which cover the early history of the children of Israel once in the land.

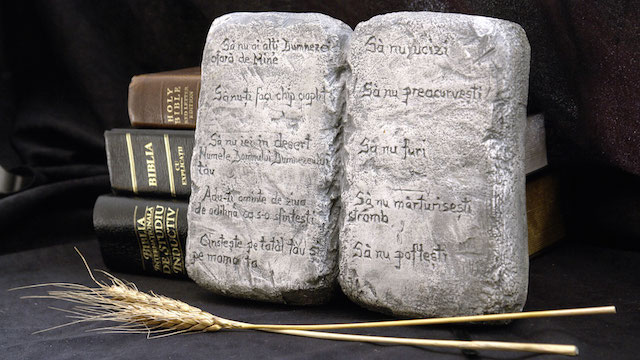

The title Deuteronomy (“second law”) is based on an error on the part of some Greek translators. They took the instruction that future kings of Israel should make “a copy of this law” (Deuteronomy 17:18) to mean “a repetition of the law” and named the book accordingly, because it does repeat many aspects of the law given in Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers. Though the repetition is not exact (much is added in anticipation of how the law would be applied in the new land), the basis of the law code, the Ten Commandments, is practically identical. The book’s Hebrew title, Devarim (“Words,” taken from the opening verse), emphasizes Moses’ role as conveyor of God’s law.

The overall themes of Deuteronomy include several reminders of the fact of the Israelites’ slavery in Egypt and the miraculous nature of their exodus; the need to be true to their divine calling to be an exemplary people obedient to Yahweh; the rejection of worship of any other gods; the coming fulfillment of the promise that they would possess an abundant land; and the ongoing requirement to teach their children the ways and laws of God.

One way to understand the flow of the book is to see it as a seven-part parallel structure. In this design Moses opens and closes the book with narratives looking backward (chapters 1–3) and forward (31–34). He provides two addresses that are prophetic in content (4 and 30). Two covenants with Yahweh are outlined: the initial one at Mount Horeb, or Sinai (5–11), and the present one at Moab (27–29). This leaves the core of the book for an extended discussion of the law code and its application in the new land (12–26).

Outlining Deuteronomy

|

A |

Opening narrative |

Deut. 1–3 |

|

B |

Opening prophetic statement |

Deut. 4 |

|

C |

The Horeb covenant |

Deut. 5–11 |

|

X |

The law code |

Deut. 12–26 |

|

C´ |

The Moab covenant |

Deut. 27–29 |

|

B´ |

Concluding prophetic statement |

Deut. 30 |

|

A´ |

Concluding narrative |

Deut. 31–34 |

Moses Addresses the Israelites

Reminding the people that their forebears had stood at the point of entering the land some four decades earlier, Moses took the opportunity to emphasize that rebellion against God’s command to proceed in faith had brought about seemingly endless wandering in the wilderness. This arduous journey need not have happened if only they had obeyed and joined in faith with the only two of twelve spies who returned from their reconnaissance with a good report (Deuteronomy 1:19–46; see also Numbers 13–14 and Hebrews 4:2, 6).

“The Lord your God is bringing you into a good land. It has streams and pools of water. Springs flow in its valleys and hills.”

When it came time to enter the land, God had led them to defeat two kings and their peoples on the east side of the Dead Sea and the Jordan River (Deuteronomy 2:26–33; 3:1–7) and had given their land to people representing three of the tribes of Israel: Reuben, Gad and Manasseh (3:12–17).

Moses himself would not be able to cross the Jordan and enter the land. Instead his assistant Joshua would lead the people. This change was God’s decision because of Moses’ presumption in suggesting that he, rather than God, would provide a miraculous flow of water for the thirsty people (verses 23–29; Numbers 20:10–13).

Moses went on to outline the relationship between Yahweh and Israel, focusing on the centrality of His law encapsulated in commandments and statutes. If they would obey the law in the new land, other nations would say, “Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people” (Deuteronomy 4:6). But if they would disobey, Moses prophesied that great trouble would come on them. They were to recall how God had given His law at Mount Sinai, and they were to teach His principles to their children from one generation to another (verses 9–14).

“In Deuteronomy, nothing motivates Moses more than the need to overcome the people’s failure to recognize God’s capacity to meet all their needs.”

If they fell into idolatry and the worship of other gods, they would suffer great loss: “You will soon utterly perish from the land which you cross over the Jordan to possess; you will not prolong your days in it, but will be utterly destroyed. And the Lord will scatter you among the peoples, and you will be left few in number among the nations where the Lord will drive you. And there you will serve gods, the work of men’s hands, wood and stone, which neither see nor hear nor eat nor smell” (verses 26–28). If such a fate befell them, then they would still be able to call out to God, repent and become obedient, and He would rescue them. He would do this because of the covenant He had made with their forefathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (verses 29–31).

Extending the Sinai Covenant

In chapter 5, the Ten Commandments previously given at Mt. Sinai (see Exodus 20) are repeated almost verbatim, the major differences being an emphasis on the escape from Egypt. In reiterating the basic law, Moses made a connection between Sabbath-keeping and release from Egypt. Just as the Sabbath signifies rest and freedom from everyday work, so the Exodus represented escape and freedom from the oppression of an ungodly society. In the book of Exodus the reason given for Sabbath-keeping is related to God’s six-day work of creation and His resting on the seventh, thereby creating a weekly day of rest for humanity. In each book a different Hebrew word is used in reference to the intended human response to the Sabbath. Exodus specifies remembrance of the Sabbath as a memorial of God’s creation work and subsequent resting, whereas Deuteronomy points to observance of the Sabbath as a reminder of God’s work in freeing Israel from slavery.

Israel was to teach their children the law of God so that their descendants would never forget the God who had freed them from Egypt and who would keep His promises to multiply their offspring and bring them into the land He had pledged to their forefathers (Deuteronomy 6:3–7). They were to learn the cost of disobedience in the wilderness, where they had complained against God and the leaders He had chosen (verse 16). Their children would be blessed for not repeating such defiance, and when they would ask about the reason for and meaning of the law code of Israel, their parents were to reply: “We were slaves of Pharaoh in Egypt, and the Lord brought us out of Egypt with a mighty hand; and the Lord showed signs and wonders before our eyes, great and severe, against Egypt, Pharaoh, and all his household” (verses 21–22). Again, the seminal event of the time was God’s deliverance of Israel from Egypt and their arrival at the Land of Promise, with the consequent need to pass that truth on from generation to generation while never professing loyalties to other gods.

“Moses stands before the people as pastor, delivering his final sermons at the command of Yahweh and pleading with the Israelites to remain faithful to their God once they cross the Jordan and settle down in the land promised to the ancestors.”

The potential for such disloyalty was very real, because entry into the land would bring the Israelites into contact with other peoples living there. Israel was to avoid intermarriage, worship of their gods, and making covenants with them.

Important for Israel to realize was that God chose them not because of their numbers; they were, in fact, a small nation. The only reasons for God’s choice of Israel were His love and His faithfulness in keeping His promises (Deuteronomy 7:6–8). If, as God’s chosen people, they would be obedient, they would be protected from illness and have abundant crops and herds (verses 12–15).

They were not to fear dispossessing the local peoples from the land that God had promised to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob in earlier times. But as Moses reminded them, it would be God who would “drive out those nations before you little by little; you will be unable to destroy them at once, lest the beasts of the field become too numerous for you” (verse 22). The local peoples would be driven out for their wickedness, not because God considered Israel particularly righteous; in fact, they were in God’s estimation “a stiff-necked [stubborn, rebellious] people” (see Deuteronomy 9:4–6).

Blessings and Forgetfulness

The land would be a great blessing after the 40 years in the wilderness; “For the LORD your God is bringing you into a good land, a land of brooks of water, of fountains and springs, that flow out of valleys and hills; a land of wheat and barley, of vines and fig trees and pomegranates, a land of olive oil and honey” (Deuteronomy 8:7–8).

They were never to forget the great deliverance and the wealth and prosperity they would enjoy. If they became ungrateful and forgot the source of their blessings, they would face dire consequences: “Then it shall be, if you by any means forget the Lord your God, and follow other gods, and serve them and worship them, I testify against you this day that you shall surely perish” (verse 19).

God likewise warned them against memory lapses that might extend to forgetting their rebellions in the wilderness. A recurring aspect of Israel’s history was and would continue to be their rebellious nature: “Remember! Do not forget how you provoked the LORD your God to wrath in the wilderness. From the day that you departed from the land of Egypt until you came to this place, you have been rebellious against the Lord” (Deuteronomy 9:7; see also verse 24).

Moses reminded the people of the very difficult situation following the initial giving of the Ten Commandments, when he returned from Mt. Sinai to find that Israel had corrupted themselves and were worshiping a metal idol, a golden calf (verses 15–21). He reminded them of their rebellion in four more places (verses 22–23). Moses had pleaded to God for their forgiveness, and because of God’s mercy they were alive still. He now asked: “What does the Lord your God require of you, but to fear the Lord your God, to walk in all His ways and to love Him, to serve the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul, and to keep the commandments of the Lord and His statutes which I command you today for your good?” (Deuteronomy 10:12–13).

“Your fathers went down to Egypt with seventy persons, and now the Lord your God has made you as the stars of heaven in multitude.”

Now at the edge of the Promised Land, they had become what God had promised to Abraham—a nation: “Your fathers went down to Egypt with seventy persons, and now the Lord your God has made you as the stars of heaven in multitude” (verse 22).

They were to go over the Jordan and possess a land unlike Egypt, which was watered by the streams of the Nile delta in an annual flood. The land they would inherit was “a land of hills and valleys, which drinks water from the rain of heaven, a land for which the Lord your God cares; the eyes of the Lord your God are always on it, from the beginning of the year to the very end of the year” (Deuteronomy 11:11–12). That land would yield its blessings for their obedience and curses for disobedience. Worship of the true God would bring abundant rain and produce. Idolatry would result in lack of rain in due season and thus crop failure (verses 13–17).

The Details

In detailing the law for Israel at the edge of the land, Moses brought out important aspects of life in what was designed to be a theocratic society. It would include a central location where annual festivals would be held. This would separate the people from any remnants of idolatry in a land that boasted many centers of pagan worship (chapter 12). The dangers posed by false prophets and those (including even close family members) who would entice the people to follow false gods is dealt with in chapter 13. No quarter was to be given to the corrupting influence of the worship of false gods. The people were about to enter a new land with all its unfamiliarity, temptations and possibilities. Again and again Moses stressed the importance of establishing and maintaining a clear identity through identification with the one true God.

“In Deuteronomy we encounter the heart of the Scriptures that Paul characterized as an effective resource for instructing, rebuking, correcting, and training God’s people in righteousness, so that they may be competent and equipped for every good work (2 Tim. 3:16–17).”

That special identity was to be reflected in appropriate mourning; distinguishing pure from impure foods; the dedication of a tenth of one’s increase, or profits from labor, for annual festival celebration; specified support for the priestly class, widows, orphans and strangers (chapter 14); the release of debt every seven years; care for the poor, the needy, and indentured servants; and the offering of firstborn animals (chapter 15). Identity was also forged in the observance of three special annual festivals, such as the Passover, when Israel was to recall their miraculous deliverance from Egyptian slavery. This was to be followed by the Feast of Weeks in the late springtime and the autumnal Feast of Tabernacles season (Deuteronomy 16:1–17), both recognizing God’s agricultural blessings.

Another hallmark of a society based on theocratic rule was the appointment of judges who would rule with equity and fairness and without the taint of bribery (verses 18–20). Priestly or judicial decisions in difficult cases would be rendered at a central location. Similarly, future kings of Israel would have to govern fairly and impartially based on the strict standards of God’s law (chapter 17).

The priests were to have special privileges since they were given no land. Their work for all of Israel was to be recognized by gifts of money and produce, as well as parts of the animals sacrificed in religious worship. By contrast, pagan religious leaders, soothsayers, mediums, sorcerers, diviners and child-sacrificers were to be strictly avoided (chapter 18).

In the center of this material about true and false religious leaders is a prophecy about the coming of a unique prophet, like Moses but superior to him. This was later understood to be a reference to the first coming of Christ (verses 15–19).

We will continue the examination of more details of the law in the next issue as we conclude the Torah section of The Law, the Prophets and the Writings.

READ NEXT

(PART 12)