The Vision of Isaiah

The prophet Isaiah’s messages were aimed primarily at the nation of Judah, though he also directed warnings against Israel and even the surrounding nations. Ultimately, though, he delivered a message of hope and universal peace.

READ PREVIOUS

(PART 23)

GO TO SERIES

As we’ve seen in this series, part of the history of ancient Israel intersected with the pronouncements of her many prophets. Among those classified as “the Latter Prophets”—simply because they follow “the Former Prophets” in the Hebrew canon—are Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Their prophesying spanned almost 200 years, during which the divided kingdoms of Israel and Judah collapsed into irreversible spiritual decline and went into separate exiles in Assyria and Babylonia.

Here we begin an overview of the first of these three longest prophetic works in the Bible. The prophets’ role was to deliver God’s calls for personal and national change, and His messages of judgment and ultimate restoration.

Isaiah’s Message

Following his calling around 740 BCE, Isaiah was active for about 40 years in Judah and Jerusalem. Though there are references to the northern kingdom of Israel and the eventual restoration of both houses as the recombined House of Israel, Isaiah’s main focus was on the kingdom of Judah. The book’s introduction provides the historical and prophetic contours of his work: “The vision of Isaiah the son of Amoz, which he saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem in the days of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz, and Hezekiah, kings of Judah” (Isaiah 1:1).

“In both Isaiah and Jeremiah, there are passages that suggest that these prophets were advisers to the kings in their times.”

By “vision” we can understand all that he “saw” and had to say in his book, in fulfillment of a mission to warn a people grown rebellious toward their God. Other terms describing what Isaiah conveyed include the “words” (of God) and the “burden” of dire prophecies (oracles).

The prophet’s opening words address the rebellion of the children of Israel: “Hear, O heavens, and give ear, O earth! For the Lord has spoken: ‘I have nourished and brought up children, and they have rebelled against Me; the ox knows its owner and the donkey its master’s crib; but Israel does not know, My people do not consider’” (verse 2). They rebelled despite the fact that they had once promised, in covenant, to follow and obey God (Exodus 24:7–8); “All that the Lord has said we will do, and be obedient,” they had assured Moses.

If they would not repent, Isaiah was to warn them of impending judgment but also to deliver God’s promise of restoration and universal peace (Isaiah 1:16–17, 20, 24–27; 2:1–4). In chapter 2, verse 4, we read the often-quoted words declaring that future time: “They shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.”

Beyond immediate concern with Judah, another theme introduced in the opening chapters of Isaiah is the day of God’s judgment on all humanity (2:4a, 12–21).

It’s often noted that the book of Isaiah is divisible into two main sections: chapters 1–39 and 40–66. The prophet is mentioned by name in the narrative at 2:1; 7:3 13:1; and chapters 20 and 37–39). Scholars debate whether a single individual was responsible for the whole book; some have seen a second or even third compositional hand, as well as various later editors. None of this need prevent us from understanding the fundamentals laid out in the opening two chapters and expanded in what follows.

A Warning to Judah

Chapters 6–12 may be seen as another core expression of Isaiah’s message. The section begins, “In the year that King Uzziah died, I saw the Lord sitting on a throne, high and lifted up, and the train of His robe filled the temple” (Isaiah 6:1).

Despite Isaiah’s calling and commission, Judah would not be cooperative, having ears that would not hear (verses 9–10). As a result, they would have to deal with hostility from an alliance between Syria and the northern kingdom in the days of Uzziah’s grandson Ahaz (7:1–7; 8:6–7; 9:8–21).

At this point Isaiah delivered the prophecy to the king that Israel, led by Ephraim, would come to an end: “Within sixty-five years Ephraim will be broken, so that it will not be a people” (Isaiah 7:8; the prophet’s role vis-à-vis Ahaz as Judah faced invasion from the Assyrians is paralleled by the later history of King Hezekiah, to whom Isaiah was also sent; compare chapters 7 and 37). Judah would be spared if Ahaz would rely on God; if not, it would suffer punishment from the Assyrians (chapter 8).

Assyria and the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah

The period of Isaiah’s prophesying in the geopolitical context of the eighth century coincides with the expansion of the Assyrian Empire as it launched campaigns against surrounding countries.

Under Tiglath-Pileser III, or Pul (745–727 BCE), the Assyrians invaded Syria and Phoenicia. This led to some independent kingdoms, including northern Israel, becoming voluntary tributaries (2 Kings 15:19–20). In 734–732 Tiglath-Pileser moved against the northern and easternmost tribal areas of Israel, taking many captive (verses 29–31).

During this time Judah came under pressure when God allowed the northern kingdom of Israel to conspire with Syria to attack Jerusalem (verse 37; Isaiah 7). Intervening on Ahaz’s behalf, the Assyrians prevented Syro-Ephraimite success but put Judah under tribute (2 Kings 16:7–9).

Subsequent Assyrian kings Shalmanezer V and Sargon II laid siege to Samaria for three years, putting an end to northern Israel and deporting much of the population to areas beyond the Euphrates, beginning around 722 (2 Kings 17:5–6). In 701, the Assyrians came again, led by Sennacherib, and defeated all of Judah’s fortified cities (see the account in Isaiah 36–37, replicated from 2 Kings 18–19)

Isaiah also prophesied the coming of the Messiah in both a first and second coming: “For unto us a Child is born, unto us a Son is given; and the government will be upon His shoulder. And His name will be called Wonderful, Counselor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace. Of the increase of His government and peace there will be no end, upon the throne of David and over His kingdom, to order it and establish it with judgment and justice from that time forward, even forever. The zeal of the Lord of hosts will perform this” (9:6–7). That theme recurs in chapters 42 and 52–53.

Eventually even Assyria would be punished for all she had done (10:12–19).

A time of restoration will come for Israel and Judah with the end-time coming of the Messiah and the establishing of God’s kingdom on the earth (chapter 11). This section ends with a six-verse hymn of praise (chapter 12), celebrating the new world of God’s making.

The Prophet’s “Burdens”

Immediately following chapters 6–12 are passages that have both short- and long-term aspects for the world at large. “The day of the Lord” signals God’s rendering of judgment on human sin, both immediate and yet future (in what Isaiah earlier refers to as “the latter days”; see 2:2).

Beginning in chapter 13, the nations surrounding the land of Israel are dealt with in an extended prophetic cluster. First is Isaiah’s prophetic vision regarding the Babylonians, who, he writes, will be attacked by the neighboring Medes/Persians and overthrown, never to rise again (verses 17, 19–22). Then the people of Israel will have peace and celebrate liberation from the Babylonians (14:3–11).

“The burdens in chapters 13–23 show that Israel is only a part of a larger tragedy, ‘the destruction of the whole land.’”

This leads to a typological section comparing the rise and fall of Babylon’s ruler to the history of Satan—how the angelic being Heylel became God’s enemy (in Hebrew, satan), and how he will go to his ultimate fate: “For you have said in your heart: ‘I will ascend into heaven, I will exalt my throne above the stars of God; I will also sit on the mount of the congregation on the farthest sides of the north; I will ascend above the heights of the clouds, I will be like the Most High.’ Yet you shall be brought down to Sheol, to the lowest depths of the Pit” (see verses 12–21).

In the remainder of chapter 14 and continuing into chapter 19 is a list of the surrounding nations to receive God’s judgment: Babylon, Assyria, Philistia, Moab, Syria, Ethiopia and Egypt. But eventually, Isaiah writes, there will be an amicable threesome of Egypt, Assyria and Israel in the Middle East: “In that day Israel will be one of three with Egypt and Assyria—a blessing in the midst of the land, whom the Lord of hosts shall bless, saying, ‘Blessed is Egypt My people, and Assyria the work of My hands, and Israel My inheritance’” (19:24–25).

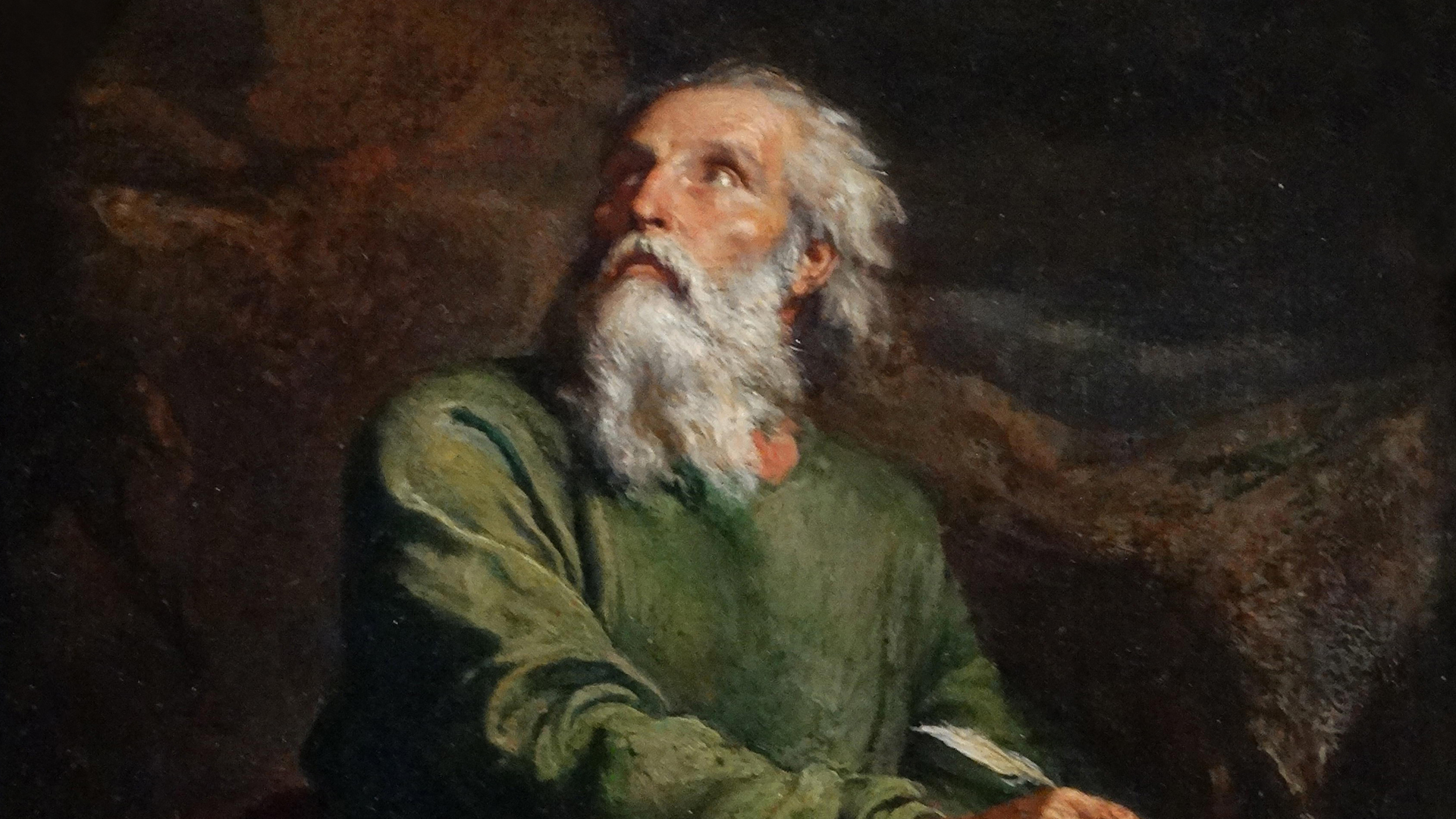

By the Waters of Babylon by Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding (1787–1855), watercolor over pencil. The painting’s theme is taken from Psalm 137, in which the Jewish exiles yearn for their homeland and for Jerusalem in particular.

Destruction and Restoration

Sometimes God required the prophets to act out depictions of coming difficulties. For example, Isaiah walked naked and barefoot for three years to demonstrate the captivity that awaited Egypt and Ethiopia at the hands of the Assyrians. This was intended as a warning to Judah not to rely on these nations for help against Assyria (chapter 20).

The prophesied punishment to come on surrounding nations to the east and south is confirmed in the next chapter. It includes oracles against Babylon, Edom and Arabia (chapter 21). The focus then narrows to the sins of Jerusalem and Judah, and even to the king’s steward, Shebna. Next Isaiah addresses other neighbors to the north, Tyre and Sidon, who will suffer for their arrogance. Seventy years of decline will come on Tyre (chapter 23), but the whole earth will eventually pay the price for sin (chapter 24). And then will come global restoration, when the veil of deceit and the curse of death that has enveloped all people will be removed (chapter 25).

Revisiting the need for rescue and the end of the wicked, the next two chapters speak of God’s salvation in the context of the ultimate “day of the Lord” and the restoring of Israel to her land.

“God affirms his care and protection for Israel, now in exile. . . . Though the people find themselves in new and strange circumstances, they are called to depend on the peace that YHWH offers them.”

Two further chapters return to God’s judgment on both houses of Israel, north and south, explaining the underlying reasons. The northerners are given to pride and alcoholic excess: “Woe to the crown of pride, to the drunkards of Ephraim” (28:1). Jerusalem is singled out because of its willingness to blind itself to obedience to God’s way: “Woe to Ariel, to Ariel, the city where David dwelt! . . . Blind yourselves and be blind! They are drunk, but not with wine; they stagger, but not with intoxicating drink. For the Lord has poured out on you the spirit of deep sleep, and has closed your eyes, namely, the prophets; and He has covered your heads, namely, the seers” (29:1, 9–10).

Trusting in help from Egypt is foolishness (30:1–7; 31:1–3). But a day will come when Israel will be restored, because God is patient and merciful (30:18–26). Though Assyria will be allowed to attack, they too will suffer defeat at God’s hands (verses 27–31; 31:8–9).

Isaiah next foretells a future godly King, who will rule righteously (chapter 32; 33:17), and a kingdom that will be always at peace (32:16–20). All nations will come to judgment (34:1–4), and neighboring Edom in particular will receive recompense (verses 5–17). Israel will become a beacon of light and God’s blessing, both physically and spiritually (chapter 35).

The history of Judah’s interaction with Assyria is taken up again in chapters 36–39. The invaders, under their king, Sennacherib, attacked and captured Judah’s fortified cities in Hezekiah’s 14th year (36:1). According to secular history, Sennacherib’s siege took place in 701, suggesting that Hezekiah came to the throne in 715. Yet the Bible’s internal dating suggests a date of 729 or 727, making his 14th year 715 or 713. The way this discrepancy can be reconciled is if Judah had kings with overlapping reigns and Israel had two kings at the same time, one west of the Jordan and another east of the river.

The recounting of this period in Judah’s history concludes the first section of the book of Isaiah. Next time we’ll look at the second, comprising chapters 40–66.

READ NEXT

(PART 25)