The Five Books of Psalms

The book of Psalms, with its varied themes fitting a great variety of human situations, is meant to be an accompaniment to daily life, with its ups and downs, its tests and trials.

READ PREVIOUS

(PART 36)

GO TO SERIES

Many people consult the book of Psalms in moments of despair, seeking comfort and guidance. Some psalms are much better known than others, perhaps because over the years people have identified the ones that give special encouragement and hope in darker moments. So within each of the five separate books that comprise the entire collection, favorites have emerged. It’s on some of these favorites that we’ll focus this time.

Aside from its two introductory psalms about the character of the godly person and the coming rule of God on the earth, the first book and much of the second are generally attributed to David, king of Israel. In this way, the entire collection begins with a point in time where the most significant God-fearing monarch in Israel’s history expresses his personality, character and love for God.

“The Psalms offer expressions of praise and prayer that have been found, over the generations, to be recurringly poignant and pertinent to the ebb and flow of human life.”

The First Book

Book 1 (Psalms 1–41) contains several psalms that have gained special attention. There is Psalm 8, a creation hymn, with its description of humanity’s privileged place in the universe. It asks, “What is man that You are mindful of him?” (verse 4). There are three other creation psalms (19 and 65 in Book 1; 104 in Book 4). These are introduced as reminders of the power of God and His overall sovereignty.

The eighth is also a messianic psalm. What makes a psalm messianic? Certainly, in the first instance, its content relates to the life of Jesus in the New Testament and is mentioned either by Christ Himself or by others. Messianic psalms may also relate to some aspect of His promised return.

Anticipating the Messiah

In a post-resurrection appearance, Jesus told His disciples that the Hebrew Scriptures had often pointed to Him: “These are the words which I spoke to you while I was still with you, that all things must be fulfilled which were written in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms concerning Me” (Luke 24:44).

The reference to “the Psalms” is shorthand for the third division of the Hebrew Scriptures known as “the Writings,” of which Psalms is the first book.

Traditionally, 14 psalms have been considered messianic: 2, 8, 16, 22, 40, 45, 68, 69, 72, 89, 109, 110, 118 and 132. Here we’ll consider just four of these compositions.

Psalm 2 speaks of God establishing His kingdom through His Son and chosen king. Though human kings may oppose God’s anointed, they will be defeated. The early followers of Christ saw this as a prophecy fulfilled in the crucifixion of Jesus by the Romans in concert with the Jewish religious and secular authorities, and in His subsequent triumph over death (Acts 4:25–28). The apostle Peter further connected Christ’s resurrection (Acts 2:22–32) with Psalm 16, which concludes: “Therefore my heart is glad, and my glory rejoices; my flesh also will rest in hope. For You will not leave my soul in Sheol [the grave], nor will You allow Your Holy One to see corruption” (Psalm 16:9–10).

Jesus Himself cried out the first words of Psalm 22 as He was close to death on the crucifixion stake: “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?” (Matthew 27:46). The reviling of Jesus by the thieves crucified with Him and by the crowd of onlookers (Matthew 27:43) is the fulfillment of Psalm 22:8: “He trusted in the Lord, let Him rescue Him; let Him deliver Him.”

Finally, Christ’s priestly descent from the line of Melchizedek is explained in Hebrews 5:6, 10 and 7:17, 21. The book of Psalms had long foretold this identification: “The Lord has sworn and will not relent, ‘You are a priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek’” (Psalm 110:4).

Psalm 15 defines godly human character and behavior. It asks, “Lord, who may abide in Your tabernacle? Who may dwell in Your holy hill?” Because of the definitive answer, this psalm is said by Jewish sages to summarize all 613 aspects of the law (by their count) in its few short verses.

Another well-known psalm helps all who are betrayed and feeling isolated; Psalm 22 also refers to the Messiah’s ultimate suffering, making it powerfully poignant: “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?”

The 23rd psalm, the most popular of all, gives comforting words about God’s care and concern for everyone who is burdened down: “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.” And for those whose life is troubled by the apparent success of the ungodly, causing disappointment and distress, there is the encouragement to “rest in the Lord, and wait patiently for Him,” because the day will come when “the wicked shall be no more” (37:7, 10).

“The psalms, as we will see, are a verbal portrait gallery of God, in that many of them provide us with a striking picture of God.”

The Second Book

Book 2 (42–72) opens with two psalms considered by some to be one continuous meditation. This is part of a sequence of compositions (42–49; 84–85; 87–88) attributed to the sons of Korah, musicians from the tribe of Levi who were responsible for community worship.

The emphasis in the beginning of the second book is on the yearning of a follower of God to come into His presence. In earlier times this encounter with God might happen at the annual holy day festivals in Jerusalem: “I used to go with the multitude; I went with them to the house of God, with the voice of joy and praise, with a multitude that kept a pilgrim feast” (42:4).

Early on, the book also pleads for help against the ungodly: “Vindicate me, O God, and plead my cause against an ungodly nation; oh, deliver me from the deceitful and unjust man!” (43:1). The experience of having to deal with the conduct of the ungodly appears often in Psalms. It’s part of the human condition, causing deep sadness. God’s help is needed: “Why do I go mourning because of the oppression of the enemy? Oh, send out Your light and Your truth! Let them lead me; let them bring me to Your holy hill” (43:2c–3).

The history of Israel as a people with whom God chose to work in a unique way is backdrop to the oppression they felt when enemies seemed to be triumphant: “You have cast us off and put us to shame;” “Arise for our help, and redeem us for Your mercies’ sake” (44:1, 9, 26). And the centrality of Zion, as the place God favored for working out His purpose, is frequently mentioned in the Korahite collections: With respect to “the city of God, the holy place of the tabernacle of the Most High,” we learn that “God is in the midst of her, she shall not be moved” (46:4–5); and “Great is the Lord, and greatly to be praised in the city of our God, in His holy mountain . . . Mount Zion” (48:1–2).

Psalm 50 is the first of several attributed to Asaph, another of King David’s temple musicians. It’s an expansive psalm speaking of God’s majesty: He “will shine forth” from Zion. This psalm also shows that God separates the righteous from the unrighteous by their response to His teaching (verses 2, 22–23). It is more evidence of the overarching theme mentioned in Psalm 1—that of the characteristics of the godly versus the ungodly.

Another favorite psalm follows and is associated with David’s sorrowful frame of mind after his infamous adultery with Bathsheba. Even if the later attribution to David is incorrect, the psalm has much to tell us about a repentant attitude before God. The admission “Against You, You only, have I sinned” is one that we must all make in coming to understand where we are “located” in respect of God when we sin. The truth is that a right relationship with Him depends on understanding that “the sacrifices of God are a broken spirit, a broken and a contrite heart—these, O God, You will not despise” (51:4, 17).

Most of the remaining psalms in Book 2 are attributed by the biblical editor(s) to David; and based on their superscriptions, many of these are tied to incidents in his life. Because we know of various events involving the king from the biblical histories of Israel, such connections are quite credible.

The second book ends with a psalm attributed to David’s son Solomon. Perhaps this is appropriate from a final editor’s perspective, since we are at the end of this independent collection of psalms assigned to David.

While the psalm’s content could describe the success and prosperity of the kingdom of Israel under David’s heir, it can also be understood as a hymn to the Messiah and His coming reign on the earth—a time of universal peace, abundance and justice. Its concluding praise is directed to this God: “Blessed be the Lord God, the God of Israel, who only does wondrous things! And blessed be His glorious name forever! And let the whole earth be filled with His glory. Amen and Amen” (72:18–19).

The final verse decisively marks the conclusion of this section: “The prayers of David the son of Jesse are ended” (72:20).

“Hymns of praise are not very frequent at the beginning of the book, but as you read on, you will find more and more of them. It is as though the more you pray, the more you will realize God’s goodness.”

The Third Book

Book 3 (73–89) reveals 11 further works attributed to Asaph (73–83). Here attention turns to the individual as part of the people of Israel, bound to God by a covenant. Just as the first two books opened by laying out two ways of life, godly and ungodly, so Book 3 begins with delineating two opposing goals: to gain the world or to gain true life. Pondering again why the wicked prosper, the writer has now become envious of their success and has almost been persuaded to adopt their ways (73:3–8).

It’s only when he visits God’s sanctuary and takes on a godly viewpoint that he begins to see clearly again, recognizing his bitterness, foolishness and ignorance (verses 17, 21–22).

But in 586 BCE, many years after Asaph, the Babylonians destroyed the sanctuary at Jerusalem. Since Psalms 74 and 79 describe that plunder, they were obviously added to the Asaphite collection later.

This is an example of an editor arranging certain psalms according to an overall design, even though they come from a different period—in this case, post-exile when the captives looked back on what had happened: “O God, the nations have come into Your inheritance; Your holy temple they have defiled; they have laid Jerusalem in heaps” (79:1).

The lengthy Psalm 78 gives an account of Israel’s history with the intent of stirring community memory of the Exodus, the wilderness years, and the entry into the Land of Promise. Despite Israel’s rebellion, ingratitude and backsliding, God is shown as the defender of His people and the promoter of Judah and David over the house of Joseph, with Mount Zion as temple location and Jerusalem as capital.

Psalms 84, 85 and 87 come from the Korahite collection and parallel Psalms 42–43, 44 and 46–48. They speak respectively of longing for the tabernacle of the Lord and express both national lament and love for Zion. A single psalm with attribution to David (86) is included in Book 3. Here he calls personally on God’s mercies. This was no doubt done by design to create a lead-in to the king’s reappearance in Psalm 89.

The book ends with psalms from two Ezrahites, men about whom little is known: Heman (88) and Ethan (89). Psalm 88 expresses the same kind of distress spoken of in Psalm 86, where God eventually provides rescue. But here, Heman cannot find help in his trial, which remains unresolved. There are times when God does not answer, and patience is required. Psalm 89, the conclusion of Book 3, is an affirmation of God’s goodness, mercy and faithfulness, and His long-term kindness toward David and his dynasty: “I will sing of the mercies of the Lord forever” (verse 1). Though there will be temporary withdrawal of blessings and covenant relationship because of infidelity, there is hope in God’s faithful promises: “Blessed be the Lord forevermore! Amen and Amen” (verses 3–4, 30–52).

The Great Psalms Scroll is among the best preserved of the numerous scrolls discovered in caves above the northwest shore of the Dead Sea between 1946 and 1956. The scroll dates from the first half of the first century CE.

The Fourth Book

Book 4 is the shortest, with 17 psalms. It begins by recalling Israel’s great leader Moses. Attributed to him, Psalm 90 is like the Song of Moses recorded in Deuteronomy 31–32. After the sadness of Psalm 88 and its unresolved ending, this psalm sets human weakness in the context of God’s eternity.

Understanding that human frailty need not be a permanent condition, the psalm gives perspective on life and suffering and the need for reliance on God: “Before the mountains came into being, before You brought forth the earth and the world, from eternity to eternity You are God. You return man to dust; You decreed, ‘Return you mortals!’ For in Your sight a thousand years are like yesterday that has passed, like a watch of the night.” This frailty is the reason to seek God’s help and mercy: “May the favor of the Lord, our God, be upon us; let the work of our hands prosper, O prosper the work of our hands!” (90:2–4, 17, Tanakh).

“The counter-world of the Psalms contradicts our closely held world of self-sufficiency by mediating to us a world confident in God’s preferential option for those who call on him in their ultimate dependence.”

In a succeeding psalm for the Sabbath day, there are seven occurrences of the name Yahweh. This connects perhaps with the establishment of the seventh day of Creation as the day of rest, accompanied by thanksgiving. Accordingly, “it is good to give thanks to the Lord, and to sing praises to Your name, O Most High; to declare Your lovingkindness in the morning, and Your faithfulness every night” (92:1–2).

Psalms 93 and 95–99 are associated with God’s kingship or enthronement. They deal with God as Creator, Judge and Victor.

A single psalm of David (101) references removing evildoers from Zion and introduces the next, where Jerusalem’s destruction is again mentioned. The exiles are anxiously longing for the city’s reestablishment: “You will arise and have mercy on Zion; for the time to favor her, yes, the set time, has come” (102:13).

Two psalms, historical in content (105–106), follow. They concern the Abrahamic covenant of promised land, still in force for the exiles who had returned to Jerusalem, and a recounting of Exodus events and the reason for subsequent exile, showing how God’s mercy will ultimately prevail: “He also made them to be pitied by all those who carried them away captive. Save us, O Lord our God, and gather us from among the Gentiles, to give thanks to Your holy name, to triumph in Your praise” (106:46–47).

Book 4 comes to a close with another form of doxology, or praise: “Blessed be the Lord God of Israel from everlasting to everlasting! And let all the people say, ‘Amen!’ Praise the Lord!” (verse 48).

The Fifth Book

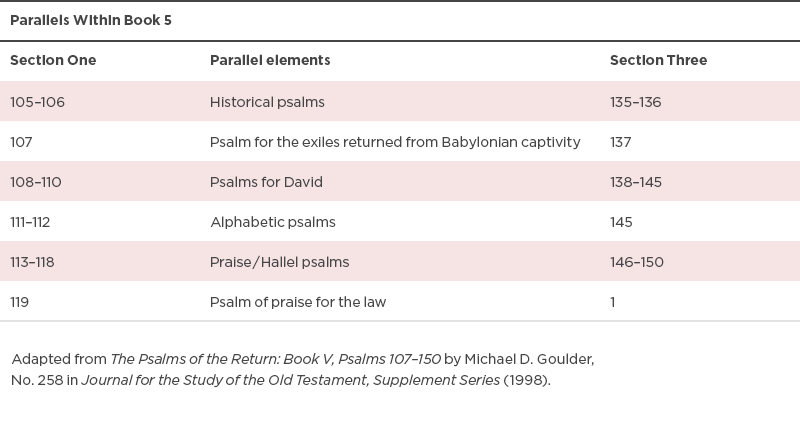

Book 5 (107–150) demonstrates a complex organization that pays tribute to the final editor(s) of the entire collection. We can think of the final book as three interrelated sections:

- 107–119, which in Jewish tradition includes what is known as the Egyptian Hallel, or Praise. This is read around Passover time, recalling the Exodus from Egypt, and comprises Psalms 113–118.

- 120–134, named the Songs of Ascents. While there is some debate, this collection relates perhaps to going up to Jerusalem for the annual holy day seasons.

- 135–150, which includes the collection known as the Little Hallel of concluding songs of praise (146–150).

Within this overall structure, there is additional evidence of intricate final editorial design of the two outer sections.

- Hebrew alphabetic patterns (acrostics) in Psalms 111 and 112 introduce the Egyptian Hallel. They are paralleled by Psalm 145, which is also organized according to a Hebrew alphabetic acrostic and introduces the final Hallelujah section (146–150) with the superscription “A Praise of David.”

- Psalms 108–110 and 138–145 are attributed to David and precede the praise portion of both sections.

- Psalms 107 and 137 refer to the Babylonian captivity and the exiles’ return.

This deliberate parallel design can be extended in two directions by considering the historical psalms that precede the two sections. At the end of Book 4 we saw that Psalms 105 and 106 discuss Israel’s history from Abraham to his settling in the land, and from the Exodus to the exile respectively. Psalm 106 ends with a prayer that God will free the captives from the nations where they have been taken. This leads into Psalm 107, which begins with thankfulness for such liberation. The third section in Book 5 opens with the only other two historical psalms in the book: 135 and 136. The latter opens with the same words used in 105 and 106; “Oh, give thanks to the Lord, for He is good!” Psalm 137 looks back on captivity from the vantage point of liberation.

But what of the well-known and popular Psalm 119—the longest, with 176 verses? Not only is Psalms in the center of the Bible, but Psalm 119, in praise of God’s law, introduces the central Songs of Ascents collection of Book 5. Does it have a parallel? The only other psalm with the theme of God’s law is Psalm 1, and this provides us with an answer. Like Psalm 119, it opens with the word Blessed. And with Psalm 1 as the final corresponding composition, the reader or worshiper is directed back to the beginning of the book, ready to begin a new annual cycle—something the returning exiles may have been encouraged to do as they reestablished themselves in the land, with rebuilt temple and renewed liturgy.

Viewing Psalms as a Whole

The book of Psalms is intended to be read as an entire work. It has many themes and types of psalms, fitting a great variety of human situations. It’s an accompaniment to daily life, with its ups and downs, its tests and trials. As one writer has said, it’s “a little Bible”—a summation of all that makes up life as humans progress toward God’s salvation.

Any one of the five praise psalms that complete the book would provide a suitable conclusion to this overview. The one that introduces the finale (Psalm 146) reminds us of who we are, where we are presently located, and on whom we must rely. From the Tanakh version:

“Hallelujah. Praise the Lord, O my soul! I will praise the Lord all my life, sing hymns to my God while I exist. Put not your trust in the great, in mortal man who cannot save. His breath departs; he returns to the dust; on that day his plans come to nothing. Happy is he who has the God of Jacob for his help, whose hope is in the Lord his God, maker of heaven and earth, the sea and all that is in them; who keeps faith forever; who secures justice for those who are wronged, gives food to the hungry. The Lord sets prisoners free; the Lord restores sight to the blind; the Lord makes those who are bent stand straight; the Lord loves the righteous; the Lord watches over the stranger; He gives courage to the orphan and widow, but makes the path of the wicked tortuous. The Lord shall reign forever, your God, O Zion, for all generations. Hallelujah.”

The book of Psalms concludes with Israel in a postexilic setting. Freed from Babylonian captivity, the returnees to Jerusalem gathered to set up a renewed society with God at its center.

In the final part in this series, we’ll survey the remaining book in the Writings, the historical and prophetic book of Daniel. From its opening in Babylon to the coming of the Persians, then the Greeks, and finally the Romans, Daniel bridges the intertestamental period and far beyond.

READ NEXT

(PART 38)