The Precarious Path to DNA’s Promised Land

Sequencing, decoding and ultimately altering our DNA to improve and enhance the human condition is the promise of 21st-century biotechnology. Will new gene-editing tools strengthen our resolve for genetic freedom? Or should these discoveries give us pause to consider other paths forward?

The biblical story of the Exodus seems far removed in both time and meaning from the 21st century. Yet the idea of release from captivity and the hope of a Promised Land are anything but dated.

The high points of the iconic story are well known and can serve to frame our modern iteration of the journey. Around 3,500 years ago, God recruited Moses and, through a series of miraculous plagues, persuaded Pharaoh to “let My people go.” Following a pillar of fire by night and of cloud by day, the Israelites passed through the Red Sea, received the Ten Commandments, and eventually, after much backpedaling and suffering, entered the Promised Land along the eastern Mediterranean. To leave Egypt and worship God in their own land was their promised destiny.

Today we are involved in a different type of exodus. Casting our vision and hopes on a biological pillar, the DNA helix, humankind has embarked on an equally challenging and miraculous journey: an escape from the Egypt of our own genome. Our modern hope is for liberation from ill health, degeneration and the biological clock; simply put, we desire nothing less than long lives without disease for ourselves and our children.

Genetic Reset

Embarking on such a journey is not a new idea. In his own “Let my people go” moment, Julian Huxley coined the term transhumanism. Just as the Space Age was dawning and DNA structure had been discovered, Huxley believed we were on the cusp of a new age of man. In New Bottles for New Wine (1957), he described his vision of our “cosmic duty” to realign our new discoveries with a more powerful humanism: “What the job really boils down to is this—the fullest realization of man’s possibilities, whether by the individual, by the community, or by the species in its processional adventure along the corridors of time.”

The pace of this march is quickening. As University of California–Davis cell biologist and popular science blogger Paul Knoepfler notes, “transhumanism is alive and well today.” In its modern genetic sense, it’s a walking away from our slavery to the genes that nature hands us: “The confluence of transformative advances in genetic, reproductive, and stem cell technologies are poised to change our world and us with it.”

We are, unfortunately, “programmed to die,” says stem cell scientist Clive Svendsen. That programming is in our genes. According to evolutionary theory, we exist to propagate our genes. It is our DNA that seeks immortality, and in one sense, because we are each the product of a successful episode of reproduction, our genes have achieved their mission. Each of us is an unbroken chain stretching back through time, generation to generation as far as the imagination will allow. After we have reached maturity and reproduced a new generation, our biological task is complete.

So now we want to break the evolutionary paradigm. “In a sense,” Svendsen told Vision, “natural selection has disappeared and we really don’t need to die anymore.”

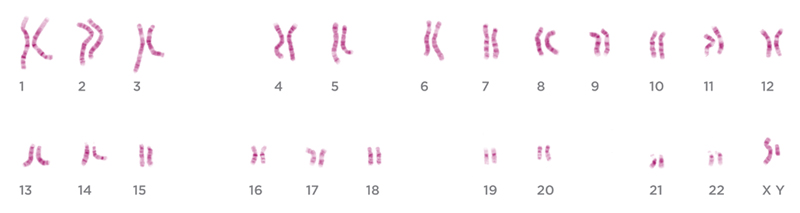

Our genes, then, not only weigh us down but, with the right reprogramming, might also set us free. Scientifically there is no place else to look if we’re going to push back our mortality and improve our livelihood. We must transform ourselves. Because we are physical beings, we are obviously in some sense bound by our biology. But ever since the discovery of the structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, the gene has loomed ever larger as the point of access—the master switch to our biological destiny.

Running With Scissors

This is no longer something only for the textbooks created by and for white-coated, blue-gloved genetic monks in cloistered laboratories. Revolutionary advances in gene sequencing, data mining and digital processing are occurring exponentially. And this makes genetic information increasingly marketable and publicly available. For example, 23andMe, a direct-to-consumer DNA-testing company, aims “to help people access, understand and benefit from the human genome.”

Showing a level of confidence in the core processes of genetic analysis that has not been seen before, the US Food and Drug Administration recently granted approval to the company’s product. The FDA’s press release noted that it has “today allowed marketing of 23andMe Personal Genome Service Genetic Health Risk (GHR) tests for 10 diseases or conditions. These are the first direct-to-consumer (DTC) tests authorized by the FDA that provide information on an individual’s genetic predisposition to certain medical diseases or conditions, which may help to make decisions about lifestyle choices or to inform discussions with a health care professional.”

Thus, as DNA has moved to center stage biologically, its role and power have become more apparent to a larger audience. Like a beacon, it demands all eyes and will be increasingly hard to ignore regardless of our personal interest in cells or chemicals. We are naturally curious about our family’s history. Now we have a window into its future.

This opportunity to know in a scientifically validated way is fueling a growing desire to fix, intervene and bargain with fate. The omniscient and enslaving genetic pharaoh is morphing from inflexible oppressor to a kind of grumpy but pliable grandfather, apparently more easily manipulated than at first believed. With new gene-editing technologies such as CRISPR (a protein that can be set up to cut and splice DNA in a precise way), it appears that we will be able to repair what is broken. Even more, we’ll be in a position to negotiate and redesign the future rather than simply waiting for its biological unfolding.

“Human curiosity and ingenuity have discovered a simple, effective means to snip out nature’s mistakes from the grammar of the human genome, and to substitute correct sequences for incorrect ones,” write Sheila Jasanoff, J. Benjamin Hurlbut and Krishanu Saha. “CRISPR-Cas9 offers, at first sight, a technological turn that seems too good for humankind to refuse. It is a quick, cheap, and surprisingly precise way to get at nature’s genetic mistakes and make sure that the accidentally afflicted will get a fair deal, with medical interventions specifically tailored to their conditions. Not surprisingly, these are exhilarating prospects for science and they bring promises of salvation to patients suffering from incurable conditions.”

It is a profoundly exciting proposition to imagine escaping our inner Egypt of broken DNA. Through our own set of biotechnological miracles, amassed over the past few decades, we are seeing the double helix in a new light. Jasanoff notes, “Transcending the human condition is partly about physical escape from death and other chafing limits on human abilities, such as forgetfulness, pain, and disability, but transcendence also has a salvationary appeal. . . . With science and technology as ready servants, that wish for perfection comes within reach: in the modern posthuman imaginary, what should be can be.”

Rather than being locked down to a genetic fate, the helix has turned its other face: the face of malleability—and with malleability, hope.

“But,” Jasanoff, Hurlbut and Saha warn, “excitement should not overwhelm society’s need to deliberate well on intervening into some of nature’s most basic functions.”

“Let us not be deluded . . . that the renewed debate about germline genetic engineering, prompted by CRISPR/Cas9, is about rescuing a small number of individuals from the burden of genetic disease. It is nothing less than a debate about what it will mean to be human in the future.”

Neo-Eugenics

Huxley recognized the unease that would occur as new opportunities appeared: “People are determined not to put up with a subnormal standard of physical health and material living now that science has revealed the possibility of raising it. The unrest will produce some unpleasant consequences before it is dissipated; but it is in essence a beneficent unrest, a dynamic force which will not be stilled until it has laid the physiological foundations of human destiny.”

As sociologists and science historians Dorothy Nelkin and M. Susan Lindee noted in their 1995 book, The DNA Mystique, we have drifted toward endowing the double helix with godlike powers. At that time, in the early years of the Human Genome Project (HGP) to sequence all three billion DNA bases of our genome, they foresaw its enticing glow: “The status of the gene—as a deterministic agent, a blueprint, a basis for social relations, and a source of good and evil—promises a reassuring certainty, order, predictability, and control.” But the hope of “certainty” and “order” are not inherent in the molecule itself. These are, instead, qualities that we will need to impart to it; DNA is a wild thing, and we must learn to tame its mutable, fickle and multifaceted powers: “Increased authority and power are therefore vested in scientists and physicians, who become the managers of the medicalized society.”

More than 20 years later, the HGP has given us an ever more finely grained view of our DNA code, and we have all become more charmed by the popular narrative of control. When we add CRISPR or other editing techniques into the mix, we draw even closer to the goal of human redesign. Lindee told Vision, “The funny thing is that we thought our book would quickly become obsolete, so we had to rush to get it out. Now it seems like the trends we were picking up on have grown even more powerful, and DNA is marketed to consumers and patients in ways that would be funny if they were not sad.”

Lindee notes that the “limited and probabilistic” nature of genetic information should reasonably put a damper on the hype. But as Nathaniel Comfort, Johns Hopkins University professor of medical history, writes, the HGP “has enabled eugenicists to come out of the closet. The fantasy of controlling our own evolution is alive and well.”

This was true even before genes were known; the desire for human perfection, Comfort says, has been a kind of eugenic impulse infusing our character. Further, he writes, “even at the beginning of the [20th] century, advocates of hereditary health made promises identical to those we hear today: genetics would make us healthier, longer-lived, smarter, happier—better.”

Comfort sees bioengineering as the present morph of eugenics, a kind of neo-eugenics. With regard to the potential today for gene editing, Comfort told Vision, “It’s always hard to read the historical significance of an event while it is happening, but CRISPR seems to be the kind of breakthrough technology that could lead to commonplace genetic engineering.”

“Biological engineering starts with the insight that we are far from realising the full potential of [our] organic bodies.”

Bringing “the DNA mystique” forward to the present, Comfort notes that there is “pressure to race ahead because of scientism and technophilia. CRISPR is seen as a massive moneymaker. It is further driving us toward profitable high-tech solutions to health problems rather than the unsexy ones like reducing poverty; improving sanitation and education; addressing racial and social health disparities. I don’t like to see care driven more by share prices than by patients’ needs.”

He adds, “I voice these concerns not in some futile attempt to yank the emergency brake on biomedicine; rather, my goal is to quell the hype so that powerful technologies such as CRISPR are used humanely—to put people ahead of profits.”

The Transhuman Goal

Although only rudimentary aspects of the structure of DNA were understood by Huxley and his contemporaries, he seems prescient in describing biotech’s parting of the genetic waters. “The zestful but scientific exploration of possibilities and of the techniques for realizing them will make our hopes rational,” he believed, “and will set our ideals within the framework of reality, by showing how much of them are indeed realizable.”

The potential for gene editing—even human germ-line editing, with the prospect of actually deleting disease code from a family line—will arguably place genetic destiny under our control. Manufacturing and editing egg and sperm cells is on the horizon, and creating children with the DNA of three parents (a mother’s DNA, a father’s DNA, and a donor egg’s mitochondrial DNA) has already been accomplished. Human embryos destined (or not) for in vitro fertilization/implantation are routinely probed for the presence of genetic flaws. While we are initially hesitant and certainly will debate for some time the path to take, many are confident of the final decisions and the course we will follow.

“I think that human germline engineering is inevitable, and there will be basically no effective way to regulate or control the use of gene editing technology in human reproduction,” says J. Craig Venter in Nature Biotechnology. One of the main players in advancing the HGP, who has since sponsored the development of synthetic cells, Venter’s views have the ring of reality. “Our species will stop at nothing to try to improve positive perceived traits and to eliminate disease risk or to remove perceived negative traits from the future offspring, particularly by those with the means or access to editing and reproductive technology. The question is when, not if.” He goes on to warn, however, that “only by greatly increasing our understanding of the human genome . . . and the consequences of making changes will we have the knowledge to make wise decisions. Until that time, human genome editing should be considered random human experimentation.”

Sounding a similar alarm is Marcy Darnovsky, executive director of the Center for Genetics and Society. She noted at the 2015 International Summit on Human Gene Editing that “permitting human germline gene editing for any reason would likely lead to its escape from any kind of regulatory limits, to its adoption for enhancement purposes, and to the emergence of a market-based eugenics and . . . unacceptably dangerous social consequences.”

Old Bottles and New Bottles

Like sociologist Jasanoff, Venter and Darnovsky recognize human nature: if we can, we will. From Huxley’s perspective in New Bottles for New Wine, our grand new technologies (the wine) would inspire us to see ourselves and our potential in new ways, as “new bottles.” But his analogy is incomplete, because our nature has not changed. We are emboldened in our knowledge rather than humbled; our human nature has not weakened.

We can spot the problem in what Huxley described as transhumanism’s “central ordering concept”; that is, humanism itself—the belief that human destiny is in our hands alone. It’s the same thinking that disrupted the Israelites’ path and sent them off course in the wilderness. Their problem, like ours today, was an underlying unbelief in anything outside the physical. “There is one reality,” Huxley insisted, “and man is its prophet and pioneer.”

Just as the Israelites lost track of their agreements with God and came to believe that it was their human power that controlled their destiny, our belief in our science and in the reliability of human decisions continues to be our downfall. It is not that seeking improved health is somehow inherently wrong or against God’s will. It is not. Our problem is that we remain bottled up in the conviction that our choices are sovereign. The Israelites were warned about the danger of such hubris: “. . . when your heart is lifted up, and you forget the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt, from the house of bondage . . . you [will] say in your heart, ‘My power and the might of my hand have gained me this wealth’” (Deuteronomy 8:14, 17). But the admonition went unheeded.

One could say they found themselves in a New Place, but with the same Old Heart.

The idea of hereditary determinism—that genes are what make us or break us—is compelling but incomplete. We are flawed beings not because of our genes but because of our character. This is a problem beyond physical repair. Our deepest void, our most crippling malady, and our greatest need for regeneration will always be spiritual rather than physical. To be “transformed” by the renewing of the human mind, as Paul wrote, is the primary healing we need (Romans 12:2). That is not a transhumanist goal. That renewed mind is, however, the “new bottle” which can hold the “new wine” of God’s plan for creation (Matthew 9:17). With faith in that plan a person is able to stand firm even in the face of seemingly hopeless conditions such as those faced by the people of ancient Israel (Exodus 14:13–14; Psalm 33:13–22).

“I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit within you.”

The God of the Bible claims creative authority. This does not mean, however, that He is the cause of every horrible mutation that besets our physical beings; as Solomon observed, “time and chance happen to [us] all” (Ecclesiastes 9:11). There is absolutely no doubt that as a species we suffer greatly from genetic disasters. At our physical core is a DNA code. And day by day, cell by cell, and generation by generation, detrimental changes are occurring. Our Creator is not unaware. But we are not that code.

The ultimate exodus is to be free from the fear of death and disease. Both are real and impose pain and suffering on our lives individually and collectively. There is a future time, however, when the pain will vanish, and even the suffering that the whole of physical creation presently endures will be set right (Romans 8:18–22; Revelation 21:1–5).

We envision DNA engineering leading us to a genetic Promised Land of our own design. That land is a mirage; it will forever be just beyond our fingers. No matter what we come to achieve in our quest for human perfection—better babies, family lines, health, happiness, body image, intellect, longevity—it will never be enough. We will always imagine something more, a better place just over the next dune. And even reaching that next level will never satisfy; it will not replace the promise that God has actually made to creation, and to us, His children, for a restored and complete relationship with Him and then with each other (Acts 17:22–31).

His plan for each human being is not based on our sequence of A’s, T’s, C’s, and G’s; it is not based on how healthy or disabled, long-lived or short-lived we are. It is based on a spiritual relationship that exists beyond the physical. We have learned to snip and tuck, cut and splice genes. Genetic recombination is our forte. Spiritual restoration, a reconnection between the spirit in man and God’s Spirit and will, is God’s prerogative and the eventual Promised Land for all humankind (1 Corinthians 2:9–14).