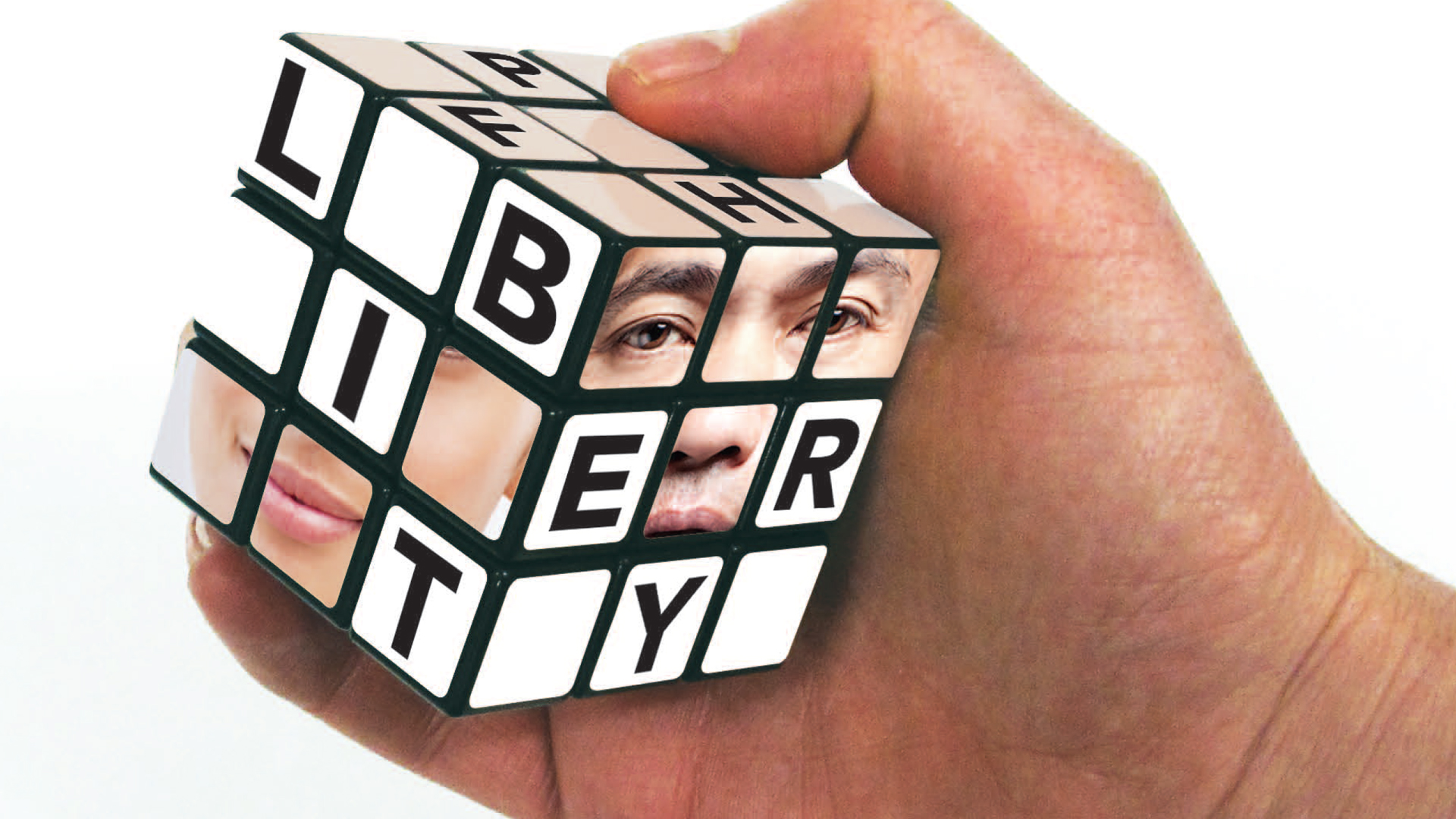

The Quest for Liberty

People all over the globe long for a system of governance that will free them, once and for all, from oppression and injustice. Yet the model for such a system was laid out long ago, along with some very personal instructions on putting it in place.

The prophet Isaiah’s depiction of a leader as a liberator contradicts all human experience. A ruler whose authority is used to give hope to the poor, heal those overcome by grief, liberate people from whatever tyranny may hold them captive, and free those oppressed by the abuse of power is almost beyond comprehension. But for that same leader to shoulder the burden of a world government, justly arbitrating between people and nations to peacefully resolve disputes and eliminate war (Micah 4:1–4), is truly unimaginable.

“The Spirit of the Lord God is upon me, because the Lord has anointed me to bring good news to the poor; he has sent me to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound.”

Our inability to conceive of that is understandable. We are generally more comfortable with the view of emperors, monarchs, presidents and prime ministers as antagonists, and it is this perception (and its historical reality) that has inspired the human struggle for liberty. Ironically, that fight has simply meant resistance to or rebellion against one imperfect ruling authority for the purpose of establishing yet another.

In its many and varied forms, representative government has become the political tool by which most people hope to construct their path to liberty. But while many societies today consent to empower their leaders to represent their nation’s interests, they restrain that power by establishing constitutional checks. We view our political leaders as delegates and servants of the community, whose power is revocable at our pleasure, especially if they fail to execute our will. One day, we hope, we’ll choose a leader who won’t disappoint, who will finally set us free from the cycle of failed government, revolution and war.

But is this really the path to freedom?

Our Own Worst Enemy

When it comes to humanity’s pursuit of liberty, too much attention has been focused on the form of government, the mechanism for limiting the exercise (or abuse) of power. In the exercise of their own will, are the governed therefore a source of rather than the solution to tyranny and oppression? And do we, in our pursuit of liberty, actually deny ourselves its freedoms and blessings?

Throughout the history of representative forms of government over the past two centuries, few people seem to have feared that we would, through our own choices, tyrannize ourselves. Perhaps as a result, such governments rule over an ever-increasing portion of the globe. But by now we have had the opportunity to observe their failings. We have learned that too often the ruling majority does oppress minorities; elected officials do vote themselves access to the public treasury; and those who represent us do construct organizations to advance or maintain their own power before they serve the public interest. Winning elections is the number one priority for representative forms of government. And when those who govern infringe on the people’s rights or violate their constitutional contract, they are not always held to answer for their wrongs, nor are they quickly and easily removed.

In summary, representative governments are not proving to be instruments of liberty as hoped. In fact, due to a fundamental flaw, they never can be.

When it comes to liberty, the real question is whether we are prepared to accept its demands. First, are we willing to submit to a leader like the one described by Isaiah? Can we accept a leader who, though untainted by human failing, isn’t democratically elected and won’t govern based on opinion polls? Are we willing to abide a social, economic and legal structure that, in the name of liberty, restricts our personal exercise of power? It’s a critical question.

Are we prepared in our pursuit of liberty to meet the demands of one law for all, justly administered? That has to be more than a law we write; it must be a law we live—a law that requires every individual engaged in the pursuit of liberty to exercise personal leadership in support of a balanced and equitable social structure, equality in economic opportunity, and commitment to preserving the integrity of the important relationships on which community life depends. Liberty requires more than a leader who speaks with one voice and governs with one standard for all; it demands that every individual in society be committed to governing him- or herself according to that standard. Before liberty can become a state of being, it has to become a state of mind.

What, then, should we do? First, we can liberate our minds by acknowledging and accepting that there is something wrong with the way we think. If it weren’t so, human history would have been something other than serial murder by war and the continuing abuse of each other in our individual pursuit of liberty and its blessings.

In order to achieve liberation, human beings will need a change of heart and mind. We will need a mind that seeks, through self-restraint, to balance rather than exploit whatever power we may have over one another. We will need humility of spirit to appreciate other people’s ability to make bad choices—choices that enslave and oppress them and others. And since we are all subject to misfortune and tragedy at the hand of powerful forces at work in our world, we must have the empathy to seek redemption when needed and to redeem as we are able. Moreover, beginning with family, we need individually to act to protect (and restore when necessary) the vulnerable, the poor, the weak and the disenfranchised in society.

Another Model

We began this examination in a previous issue by challenging what is fundamental to the organization of most civilized societies: the aggregation of political, social and economic power in an elite class. That construct has not served us well and deserves to be challenged.

So let’s examine another model given to another nation conceived in liberty, a nation that was supposed to write the story of freedom for all nations (Exodus 19:5). That story begins with one man, Abraham. His grandson Jacob, whose name was later changed to Israel, had twelve sons and one daughter. Although the family dwelt in ancient Canaan, now the southern portion of the modern nation of Israel, a prolonged famine forced the family to emigrate to Egypt to survive. Over the course of many generations, Israel’s descendents were enslaved in Egypt, brutally oppressed and forced into hard labor to build Pharaoh’s cities. In response to their pleas for liberation, God freed them from Pharaoh’s dominion and gave them a homeland, establishing a nation where not only the Israelites but also the immigrants who accompanied them could live in freedom (Exodus 23:9; Numbers 15:16).

God required that the law of this new nation be applied uniformly regardless of one’s wealth or social status (Exodus 12:49). To ensure impartiality in judgment, bribes were forbidden (Deuteronomy 16:18–20). Liberty is possible only where there is justice and equality before the law, and the nation of Israel was to exemplify those principles.

“Equality has not been a popular idea in America because it has been unable to compete with the vision of universal and limitless economic growth.”

As an immigrant nation, Israel had no natural or legitimate claim to a homeland. Their land belonged to God (Exodus 19:5; Leviticus 25:23) and was a gift in fulfillment of promises made centuries earlier to their ancestors Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Historically, humankind has felt a sort of equality in being oppressed by landowning lords, monarchs or emperors. Israel was to experience equality in the freedom granted by their landowning God. His gift to them reinforced the fact of their complete dependence on Him as their liberator and was tangible proof of His faithfulness to them.

The land was apportioned among Israel’s tribes (Joshua 13–22) and then divided as widely as possible among each extended family household or clan. What this created was an egalitarian agricultural-pastoral economy with an essentially classless social structure. Even political power was decentralized into a network of cities (Deuteronomy 16:18). The priests and Levites, spiritual leaders in the nation, were primarily teachers and judges (Deuteronomy 33:10). They did not inherit real estate, allowing them to devote their time to the instruction and spiritual care of the community instead of tending a family farm or ranch. In return, the priests and the rest of the tribe of Levi were to be provided for from the produce and livestock of those within the district they served (Numbers 18:8–32; Deuteronomy 14:28–30). They were not political rulers (1 Samuel 8).

This structure was designed specifically to prevent the aggregation of social and political power and thus prevent one class of society from oppressing and abusing another.

The 50th Year

A key component of this agricultural-pastoral economy was a 50-year cycle culminating in “the year of the Jubilee,” which represented the completion of one generational cycle counted in seven seven-year, or sabbatical, periods (Leviticus 25:8). When the nation of Israel entered their new homeland they were to begin counting those periods (Leviticus 25:1–4). In every seventh year and again in the 50th year, the year of the Jubilee, the land and the citizens of the nation ceased all commercial planting and harvesting. The people and the land were to take time for replenishment and rejuvenation. And although there was still work to do in those years, no doubt the change in pace and purpose would revitalize the nation.

A related aspect of this economy was that, to preserve comparative economic equality in Israel, the land could not be bought and sold commercially (Leviticus 25:23). As already noted, the land belonged to God. In the event that a landholder had to relinquish his plot to a creditor because of misfortune or poor economic choices, the sale was not of the land but only of the expected yield from the land until the next Jubilee. Thus the sale price was determined on the basis of two factors: the value of the land’s anticipated yield and the number of years to the next Jubilee (Leviticus 25:16–17, 25–28). In the meantime, the law permitted the landholder to buy his property back should he accumulate sufficient resources to do so (Leviticus 25:24). The closer to the Jubilee the redemption occurred, the lower the redemption price. The farther away from the Jubilee, the greater the refund to the buyer. Until redemption by the original landholder was possible, the law imposed an obligation on the landholder’s nearest financially able relative to buy the property, thereby keeping it in the family (Leviticus 25:25). In addition, families had an obligation to care for relatives who could not provide for themselves. This meant providing productive work for which an individual was paid until the Jubilee (Leviticus 25:35–36, 39–40).

The most profound impact of the statute, however, sprang from its mandate that land return to its original title holder in the year of the Jubilee (Leviticus 25:10, 28). This legislative scheme, which restricted the alienability of property, was in fact a law of liberty. The accumulation of wealth and power through the acquisition of land was simply not permitted. Therefore there was no real estate market or land speculation. The system preserved the broad and equitable distribution of land that made economic freedom and independence possible for each family. It also protected the integrity of the family by prohibiting an ostensible act of charity on the part of a prosperous family member from becoming a land grab and a means by which wealthy family members could dominate poorer ones. All of this also served to strengthen the integrity of the larger community.

Mandated Freedom

To complete the process of liberation, every seventh year was a “year of release,” when creditors were required to remit any debt claims they had (Deuteronomy 15:1–2). The primary purpose of this law was to provide an incentive to allow the land to rest. However, the law also prevented poverty and the oppression that comes from deprivation by imposing limits on the amount of debt created (Deuteronomy 15:4). Without the incentive to lend more than a borrower could repay in a seven-year period, or the portion of that period remaining at the time the loan was made, the ill effects of irresponsible and excessive lending were averted. Observance of the complete law required making loans to needy members of the community regardless of how close in time to the year of release such a loan was made (Deuteronomy 15:7–8). And those capable of repaying their debts were not permitted to use the year of release as a means of avoiding their obligations.

Because this general cancelation of debts every seven years liberated borrowers, it had the effect of neutralizing the power of creditors over debtors (Proverbs 22:7). If a lender wanted his loan repaid in a timely fashion, it was in his best interest to do what could be done to raise the economic well-being of his borrowers.

The year following the seventh sabbatical year, the Jubilee, was to be a celebration of liberty in every sense of the word. Both the land and the nation were at rest for a second consecutive year (Leviticus 25:11–13). Free from the pressure to produce at a commercial level, time could be devoted to the all-important function of restoring, healing or strengthening family relationships to build for the future. Land that had been sold reverted to its original owners and all debts were canceled. Families separated from their land or who had to hire themselves out to a family member to preserve their economic well-being were now free to return home. Slaves were freed. It was a time when families not only returned to their land, they returned to one another (Leviticus 25:10).

In a sense, the Jubilee marked the passing of one generation and the establishment of another. Passing with that older generation were their adversity and their mistakes. A newly liberated generation inherited an opportunity to do better than the generation that preceded it—without resenting or regretting the past.

It is fitting, then, that this celebration of liberty began on the 10th day of the seventh month, the Day of Atonement (Leviticus 25:8–9), an annual day of solemn national observance. Its purpose was to make the people take time to consider any events, forces and personal choices that had separated them personally and nationally from their God and liberator and from one another. The Day of Atonement was the beginning of restitution in relationships at every level of society (Leviticus 16). The beginning of a Jubilee signaled that all had been redeemed and that life began anew.

The Jubilee, simple and yet magnificent in its conception, was freedom mandated by statute but lived as a reality only if all individuals in the nation governed themselves within the framework outlined by God. This was not government that could be delegated. Representatives could not be elected to discharge one’s responsibilities to family and to society at large. Each individual had to make government his or her purpose and mission. It was that kind of personal responsibility that marked the nation’s path to liberty, and its blessings, in perpetuity.

It’s Personal

It must be said that the path outlined for Israel would never work in our world today. Because it requires every citizen to uphold obligations that most would prefer not to accept (because, ironically, they seem to infringe on individual liberty), the Jubilee remains nothing more than an interesting concept. It is counterintuitive to suggest that liberty demands self-restraint in our exercise of personal choice. It is difficult to accept that liberty is attained and sustained only when every person in a society works to prevent harm to others—the kind of harm that comes from refusing to accept a personal obligation to shelter the vulnerable, strengthen the weak, and integrate into society the disenfranchised. Nonetheless, that is what liberty demands.

The surprising reality is that it never actually worked for Israel either. One significant omission in God’s blueprint for liberty was a bureaucracy or government agency to enforce the rules. There was no credit bureau to monitor lending and the forgiveness of debt. No authority existed to oversee land sales or redemption. There were no “Jubilee Police.”

But this was not an oversight on God’s part. Instead, it exposes a fundamental flaw in representative forms of government and underscores the fact that the only form of government capable of creating and nurturing liberty is personal and cannot be delegated. We must first govern ourselves, and then we must obligate ourselves to perform the legitimate functions of government on behalf of society at large when and where we can. A failure to do so leads inexorably to the creation of bureaucracies to fill the gaps.

One lesson to be learned from the continuing global economic crisis is that a decline in self-government forces society to create governors, adopt regulations, write law, and establish endless bureaucracy to stabilize society. Sir Edmund Burke said it this way: “Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere, and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without. It is ordained in the eternal constitution of things, that men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge their fetters.” The greatest tyranny, in other words, is self-imposed (see “Economic Tyranny by Choice”).

“Men are qualified for civil liberty, in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains upon their own appetites.”

Government cannot be delegated if liberty is to reign. History demonstrates that man’s forms of government cannot solve problems that are, at their root, moral in nature. Our attempts at such manipulation have only ever produced vast, intrusive and costly governments that impotently preside over chaotic and decaying societies. So civilizations, empires and nations rise and fall. And they will continue to do so until the Jubilee that is just over the horizon—that ultimate time of release—becomes a reality (Romans 8:22–23). When that occurs, the leader that the prophet Isaiah wrote about will usher in a new generation. At that time the earth and its inhabitants will have not only the liberty they have long sought, but also its blessings.