Who Is in Control?

The Message of Daniel

The final installment in the series examines the multifaceted book of Daniel, which serves as a bridge from the Old Testament to the New.

LEER ANTERIOR

(PARTE 37)

IR A SERIE

Who has not heard of the deliverance of Shadrach, Meshach and Abed-Nego from the fiery furnace, or the protection of Daniel in the lion’s den? These stories are familiar from childhood. Equally, Daniel’s prophetic deciphering of the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar’s dream of a great metal statue is well known. Yet overall, the book of Daniel is puzzling on several levels.

It appears not among the Prophets section of the Hebrew Scriptures, but within the Writings. While the title suggests that Daniel was the author, and Jesus mentioned his book as prophecy, the first half (chapters 1–6) is written in the narrative genre about Daniel and his three friends through six individual stories. The second half (7–12), composed in the apocalyptic genre, is by Daniel as he records four separate prophetic visions.

Though six of the book’s chapters and a portion of a seventh are written in Hebrew (1, 2:1–4a, 8–12), the rest are expressed in Aramaic (2:4b–7), the lingua franca of the time. Yet this unusual division of biblical languages does not neatly line up with the two genres as one might anticipate. The narrative and prophetic sections contain material in both languages.

Further, scholars have labored over the date of authorship and the intended audience. Here we take the view that the book was written in the sixth century BCE and that its initial audience was the exiled Jewish community of Daniel’s time.

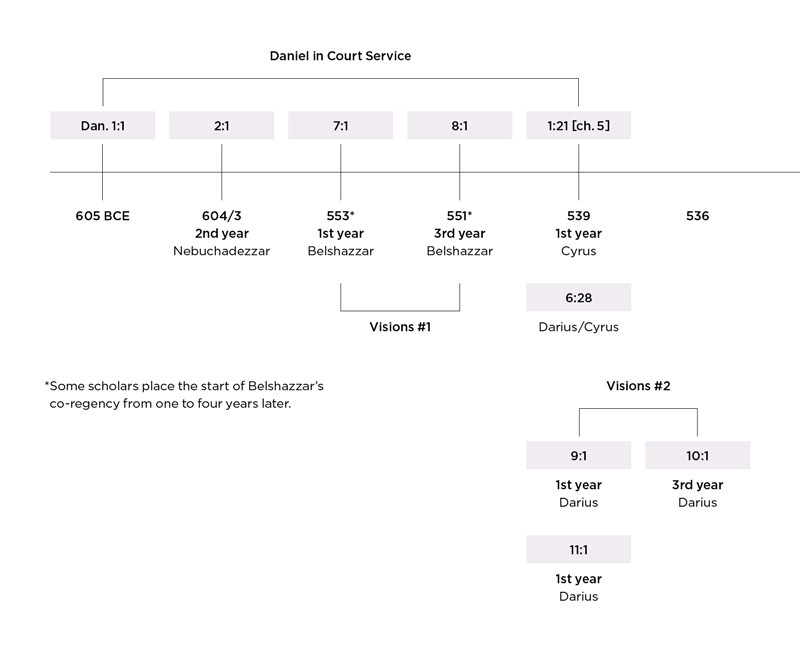

Despite the difference of scholarly opinion over these and other questions, there is much to learn from a book whose time horizon stretches from 605 (Daniel 1:1) to 537 BCE (10:1), and on into the 21st century, which may prove to be what the book refers to as “the time of the end” (see “Empires, Rulers and Events in Daniel: History and Interpretation”). This far-future focus makes the book an appropriate conclusion to this series on the Law, the Prophets and the Writings.

A more detailed look at the work’s structure and setting helps us understand its central unifying theme—that despite all that happens in life, including the conflict between God’s faithful people and pride-filled and often cruel rulers, God is in control of human destiny. Other aspects that bring the two halves of the book together include the similarity between the visions of chapters 2 and 7, identifying successive world empires.

“We do not grasp the book’s relevance by fighting the battles of historical criticism; eventually, the message of this book is revealed to those who would attempt to share its author’s vision.”

The Narrative Chapters

As chapter 1 opens, we read of the first of Nebuchadnezzar’s invasions of Judea and King Jehoiakim’s subordination, resulting in the removal of nobles, princes and members of the king’s family to Babylon. Some of these exiles are chosen for a three-year education program in Babylonian culture, wisdom, learning and language. In this we see God granting favor to the captives in the eyes of their Babylonian overlords. Despite the struggle and discouragement of exile, not all is going wrong for the Jewish captives.

Among those selected are Daniel and the three friends mentioned above. After their period of training, they are invited into the king’s presence: “And in all matters of wisdom and understanding about which the king examined them, he found them ten times better than all the magicians and astrologers who were in all his realm” (1:20).

The Hebrew language of the first chapter, a logical choice for the introduction of teaching for a Jewish audience, continues only as far as verse 4b of the second. Here the Chaldean advisors to the king address him in Aramaic. The king has had a troubling dream and demands to know its content and meaning—an impossible task that can be resolved only by God’s inspiration of Daniel (2:19–23).

The use of Aramaic continues through the following narratives about Daniel and his colleagues, perhaps to support the authenticity of the accounts that take place in gentile Babylon and that also relate to several successive world empires. Continuing in Aramaic, the apocalyptic seventh chapter serves as a bridge to that genre, which fills the remaining five chapters in Hebrew.

Here it’s helpful to detail the content and mirroring structure of chapters 2–7 as we learn about God’s sovereignty over nations and rulers in defense of His people.

Structure of the Aramaic Chapters in Daniel

| A | Chapter 2: Four empires and the coming kingdom of God |

| B | Chapter 3: A trial by fire and God’s protection |

| C | Chapter 4: A king warned, repentant and delivered |

| C' | Chapter 5: A king warned, unrepentant and removed |

| B' | Chapter 6: A trial by wild animals and God’s protection |

| A' | Chapter 7: Four empires and the coming kingdom of God |

The outer frame of this literary design (A, A') emphasizes four world kingdoms beginning with Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylonian empire, the head of gold of the great statue seen in the troubling dream. The others are, in sequence, the silver Medo-Persian empire, the bronze Greek empire, and the iron Roman empire (2:31–33, 37–43).

Importantly, no one empire lasts forever. Each is conquered by a succeeding power. But finally, the entire statue is toppled and crushed by an external force, symbolized by a great stone of nonhuman origin.

The parallel details of Daniel’s visionary dream in chapter 7, where the empires are represented by four mystical wild animals, also show the forthcoming destruction of the world’s cumulative systems by nonhuman—that is, divine—intervention. The four world systems, symbolic of all ungodly human rule, will ultimately be replaced by the everlasting kingdom of God, reigned over by the returning Son of God (7:13–14, 26–27).

The inner frame (B, B') concerns godly individuals who are opposed by ungodly individual kings. The casting of three faith-filled young men into the brutal Nebuchadnezzar’s fiery furnace, and their rescue by God, is mirrored by the hapless Darius casting Daniel into the den of lions, only to see him emerge unscathed through God’s deliverance.

Two kings, representative of human government, are at the center of the design (C, C'): Nebuchadnezzar and his descendant Belshazzar. When God warns each of them about the limits of their power, Nebuchadnezzar chooses to submit to God’s sovereignty and is rewarded accordingly (chapter 4). Belshazzar, on the other hand, being warned in the well-known account of the handwriting on the wall, defies God and receives the promised retribution: the Medo-Persians kill the king and subsume the Babylonian empire into their own (chapter 5). In all of this we see God’s control of human destiny once more.

Because a complex and disrupted chronology plays a significant role in the book, an overview may be helpful at this point.

Chronology of the Book of Daniel

Persia and Greece

In the narrative sections, Daniel has been the interpreter of dreams and events; in the apocalyptic he needs an interpreter. For each of his own four visions in chapters 7–12, an angel plays this role.

We are told that during the third year of King Belshazzar (8:1), Daniel finds himself near the ancient Elamite city of Shushan (Susa). Though the city is only a couple of hundred miles east of Babylon, it seems likely that Daniel is there in vision. Again, animals feature as symbolic of nations. He witnesses a very strong and powerful ram attacked and defeated by a more powerful and angry goat coming from the west.

The angelic interpretation and secular history confirm this confrontation as the overwhelming challenge to Medo-Persian dominance by the Macedonian conqueror Alexander the Great. Further details in the prophecy reveal that this Greek empire to come will eventually be divided into four parts, one of which will produce an unusually fierce ruler who will enter the Holy Land and desecrate the Jerusalem temple. Daniel then overhears a conversation between two angelic beings, in which he learns that this horrific event at the temple will last 2,300 days (literally “evening-mornings”). This is confirmed by the angel Gabriel, who says, however, that the fulfillment will come only in distant times (8:13–14, 26). This preview of great distress in Jerusalem troubles Daniel profoundly.

Subsequent Jewish history in the first book of Maccabees allows us to put names to these visionary events. Daniel has seen in some detail what will happen in the centuries beyond his time. Alexander’s empire did break up into four parts after his early death. As prophesied, from among the four horns, or divisions, of the symbolic goat, one leader became infamous: the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. He ordered the Jews to take up pagan religious practices in which, for example, they polluted the Jerusalem temple’s altar of burnt offering by placing another altar on top of it and sacrificing swine to Zeus. As the explanation of Daniel’s vision indicated (8:13–14, 25), the Seleucid period of desecration ended after 2,300 morning and evening sacrifices, or 1,150 days (167–164 BCE), during the Maccabean revolt, when Jewish rebels drove out their persecutors.

“The theme running through the whole book is that the fortunes of kings and the affairs of men are subject to God’s decrees, and that he is able to accomplish his will despite the most determined opposition of the mightiest potentates on earth.”

Seventy Years and Seventy Weeks

We come next to chapter 9, which concerns the revelation given to Daniel about the coming of the Messiah. This is not so much a new vision as a further explanation of what had so troubled Daniel, who turmoiled over what the attack on God’s sanctuary portended.

It’s framed by the prophet’s desire for the end of the Babylonian period of exile. He has read a preexilic prophecy (Jeremiah 25:9–12; 29:10) that mentions 70 years of desolation pronounced on Jerusalem. Knowing that the time must soon come to an end, he seeks God’s forgiveness and restoration for the nation. The punishment that had fallen on Israel and Jerusalem was the result of their breaking the Sinai covenant with God. Moses had prophesied such an outcome and the way back to God well before they entered the Promised Land (see Leviticus 26:33–35, 40–42).

Dating the end of the 70 years is not so difficult, since Daniel records his prayer in 539, the first year of Darius—perhaps a king appointed by Cyrus, or the Babylonian name for Cyrus—and the year of Babylon’s fall.

If the 70 years is a literal number, then it begins in 609, a date that has no connection with the destruction of Jerusalem. However, it was the year that Pharaoh Necho II killed the last righteous king of Judah, Josiah. God had said that despite the king’s righteousness, Judah’s punishment would be delayed no longer (2 Kings 22:16–20; 23:25–27). The Egyptian was en route to the Euphrates to support the Assyrians against the Babylonians; but they were defeated at Haran in their final disastrous campaign against Babylon. Thus 609 signaled the end of Assyria and the dawning of Neo-Babylonian supremacy.

On the other hand, if 70 is a rounded number, then 605 would be the nearest significant date, when Nebuchadnezzar’s forces came against Jerusalem the first time—66 years before 539.

As a result of Daniel’s fasting and prayer, the angel Gabriel is sent to him with a message. The answer to his concerns about the completion of the 70 years of desolation tells of a different 70 prophetic years that culminate in the coming of the Messiah. While it’s tempting to try to relate this new information to the situation in Jerusalem in Daniel’s time, the content makes it clear that it is for the intermediate and distant future. “Seventy weeks [Hebrew, sabuim, “sevens”] are determined for your people and for your holy city, to finish the transgression, to make an end of sins, to make reconciliation for iniquity, to bring in everlasting righteousness, to seal up vision and prophecy, and to anoint the Most Holy” (Daniel 9:24).

“Gabriel’s answer to Daniel’s prayer is an interpretation of the seventy years in a way that seems to extend its purview.”

Seventy sabbatical weeks (70 x 7 weeks of years) equals 490 years. This period, broken into 7 + 62 + 1 weeks, begins “from the going forth of the command to restore and build Jerusalem,” when “the street [Hebrew rehob, “open square”] shall be built again, and the wall [Hebrew, harus, “trench,” “moat”], even in troublesome times” (9:25–27).

The decree of Artaxerxes I, specifying the rebuilding of Jerusalem, was issued in 457 (Ezra 7:11–26); the city was partially repaired during the time of Ezra and further renovated under Nehemiah (Ezra 4:11–23; Nehemiah 3–7). Counting forward 69 of the 70 prophetic years (483 years) from 457 brings us to 27 CE, when we read that the Messiah will be “cut off,” but not before beginning the 70th week in which He confirms a covenant with many people (Daniel 9:26). Christ was killed by crucifixion, cut off, after 3½ years of public ministry, bringing “an end to sacrifice and offering” (verse 27) and inaugurating the new covenant with His people.

The angelic explanation also contains a message about yet another desecration of Jerusalem, of which Antiochus’s sacrilege is a type. Inserted into the message about Christ’s sacrificial death is a cryptic statement that “the people of the prince who is to come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary”—a reference perceived to be about the Roman destruction of Jerusalem and the temple in 70 CE.

Troubling Times

Daniel’s next and final vision (chapters 10–12) comes in the third year of Cyrus (536), after three weeks of mourning, or fasting, to gain more understanding of God’s plan for his people. He sees a powerful angelic being, who announces, “I have come to make you understand what will happen to your people in the latter days, for the vision refers to many days yet to come” (10:14). Helped by the archangel Michael, this angelic being had been in a confrontation with the kings of Persia and with one prince, perhaps an evil spiritual power intent on thwarting God’s purpose. This resistance had continued for 21 days, the length of Daniel’s fast.

The angel continues his message in chapter 11 with more information about the demise of Persia, the rise of Greece, and its breakup into four parts (11:1–4). Two of the four are identified as the warring Ptolemaic and Seleucid empires, the “king of the South” and the “king of the North” respectively. Without naming names, the prophecy gives very specific details about the political machinations between the two powers through to the end of what is clearly the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

It is beyond the scope of this writing to list every individual indicated, but see the historical chart for an outline. Several verses do correspond to what is known from history of Antiochus IV Epiphanes’ rule. He is “a vile person” who will “seize the kingdom by intrigue,” attacking and defeating “the king of the South with a great army.” Returning to Jerusalem, he musters forces, “and they shall defile the sanctuary fortress; then they shall take away the daily sacrifices, and place there the abomination of desolation,” corrupting people “with flattery.” From here the time horizon expands to include the people of God who do “great exploits,” yet suffer over a longer period (verses 21–32).

Then “the wise among the people shall give understanding to many; for some days, however, they shall fall by sword and flame, and suffer captivity and plunder. When they fall victim, they shall receive a little help, and many shall join them insincerely. Some of the wise shall fall, so that they may be refined, purified, and cleansed, until the time of the end, for there is still an interval until the time appointed” (Daniel 11:33–35, New Revised Standard Version).

The prophecy returns next to the characteristics of the king of the North, yet he is also here a type of the arrogant ruler seen earlier among the gentile kingdoms. There will be others like him in history until the time of the end: “The king shall act as he pleases. He shall exalt himself and consider himself greater than any god, and shall speak horrendous things against the God of gods. He shall prosper until the period of wrath is completed, for what is determined shall be done” (verse 36, NRSV).

The angel’s message is moving quickly to its conclusion. In the future, just before the climax at the close of this age of man, the two kings will fight once more. The end-time successor of the king of the South will attack the king of the North, who will defeat him and once more enter the ancient land of Israel. While various countries will be caught up in this war, some neighboring Transjordanian states will escape. Angered by news from the north and east, he will go on the attack, setting up headquarters in Israel, “yet he shall come to his end, and no one will help him” (verses 40–45). The identity of these descendants of the Seleucid and Ptolemaic rulers is not clear from Daniel’s writings, but their final actions precede the end of this age.

The closing chapter begins, “At that time Michael shall stand up, the great prince who stands watch over the sons of your people; and there shall be a time of trouble, such as never was since there was a nation, even to that time” (12:1).

“Although I heard, I did not understand. Then I said, ‘My lord, what shall be the end of these things?’ And he said, ‘Go your way, Daniel, for the words are closed up and sealed till the time of the end.’”

This part of the book explains that after the climax at the end, there will be a resurrection to life for some and to shame for others. Daniel is told to close the revelation until that time when God chooses to bring everything to a conclusion. In the meantime, Daniel will die and await resurrection to life, “for you shall rest, and will arise to your inheritance at the end of the days” (12:13).

He has asked how long before the seventy years of desolation are completed. He has heard about another period of seventy, equivalent to 490 years until Christ’s first coming. He has been told that even that time will be interrupted by a cutting off of the Messiah in the midst of the week. As a result, there are implications for the completion of the second part of the final week. Since Christ could not specify the date of His return, something only the Father knows, His final words to His disciples—“Remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age” (Matthew 28:20, NRSV)—may imply that the second half of that prophetic week symbolizes the work of Christ among His people until His return.

As for the political system of which the Seleucids and Ptolemies were a part, its collapse began in the first century BCE and gave way to the Roman Empire, the fourth wild animal of Nebuchadnezzar’s and Daniel’s visions. Unlike the other empires before it, it has undergone revivals through the ages, has reappeared and disappeared, and is prophesied to continue until the coming of the kingdom of God.

The continuation of this story is picked up in the New Testament’s final book, “The Apocalypse,” or book of Revelation.

The remarkable testimony of Daniel takes us forward from the Babylonian exile through intertestamental times to the first century CE, and on to the end of this present age. Daniel’s question about the timing and outcome of God’s plan for His people remains to be fully answered, but the book’s underlying theme is clear: God is always in control.