Rethinking Monotheism

To better understand monotheism, we need to move beyond simple numbers.

For most people monotheism is a straightforward concept: the belief in one God as opposed to many gods. This numerical approach—one versus many—has long been used to distinguish the major Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism and Islam) from ancient pagan traditions. But this seemingly simple definition becomes remarkably complex when examined closely, revealing that the nature of divine unity may be far more nuanced than a mere counting exercise.

The term monotheism does not appear in the Bible, and controversies over whether and how accurately it describes the divine nature have persisted for millennia. A closer look at the primary sources reveals that strict numerical monotheism—the idea that there exists exactly one divine being—does not adequately capture how biblical authors understood the divine.

Consider Christianity’s later doctrinal development of the Trinity. While most Christians today profess belief in one God existing as three distinct persons (Father, Son and Holy Spirit), this theological formulation emerged centuries after the biblical texts were written. The Trinity dogma, formalized at councils including Nicea (325 CE) and Constantinople (381 CE), represents an attempt to systematize what many early Christians were coming to believe, rather than a concept explicitly taught in Scripture. This has complicated understanding of what the Bible’s writers meant by divine unity.

Similarly, even ancient pagan philosophy sometimes exhibited forms of theological unity. The philosopher Plotinus, while acknowledging multiple gods, argued that all deities emanate from what he called “the One”—a supreme, unified source. This view of the unity of god-beings suggests that the distinction between monotheistic and polytheistic traditions may be less absolute than commonly assumed.

Jewish Monotheism and Hebrew Evidence

Surprisingly perhaps, Judaism provides the most instructive rationale for rethinking monotheism. The Encyclopaedia Judaica defines Jewish monotheism not as the numerical singularity of God but as the “uniqueness” of a personal god who “excludes the existence of any other qualitatively similar being.” This definition emphasizes God’s incomparability rather than mathematical oneness.

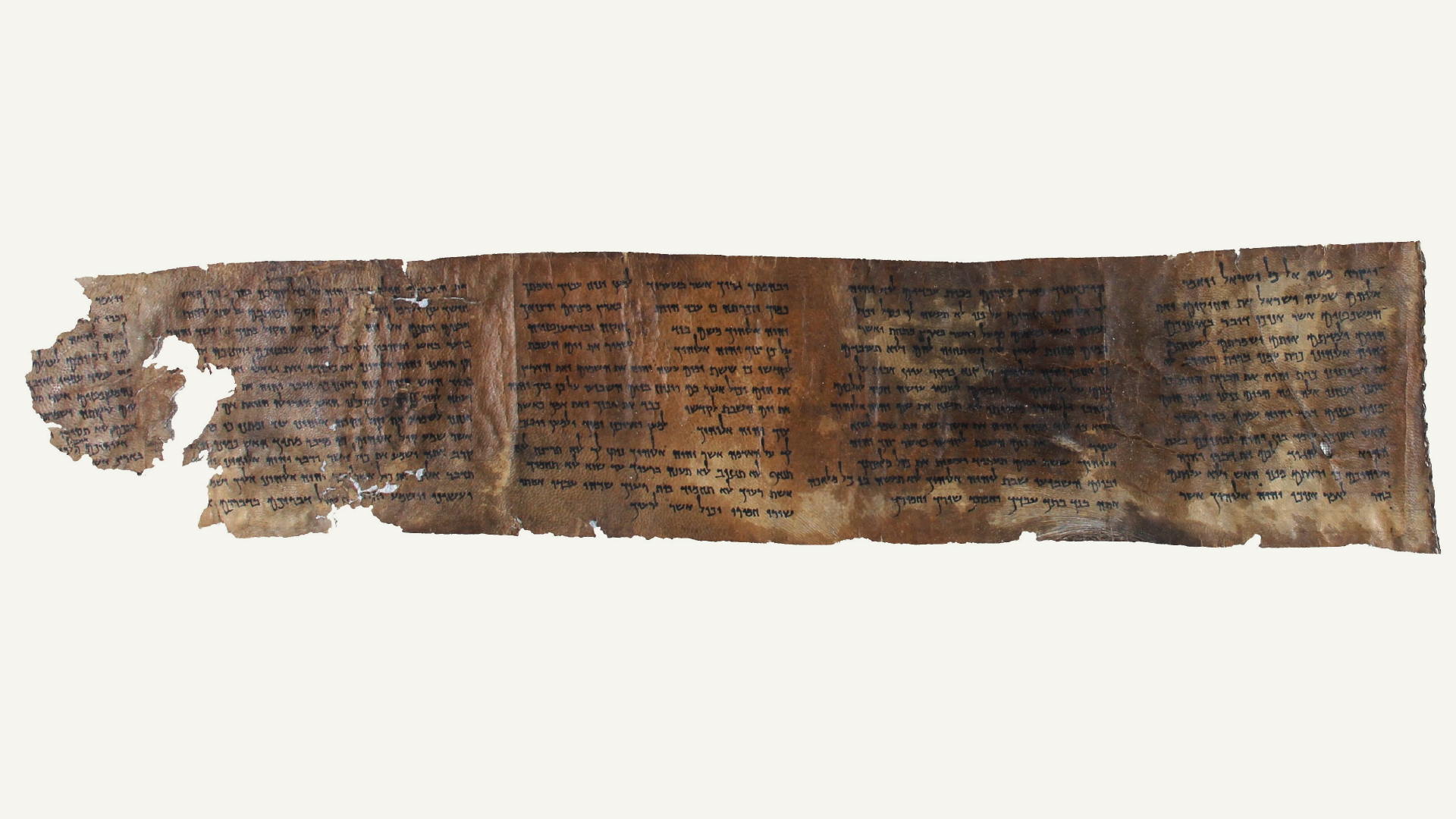

The famous Shema—“Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one!” (Deuteronomy 6:4)—is often cited as Judaism’s monotheistic declaration. But Bible scholar Jeffrey H. Tigay argues that this verse is better understood as describing “the proper relationship between YHVH and Israel: He alone is Israel’s God. This is not a declaration of monotheism, meaning that there is only one God.”

“Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one!”

Zechariah 14:9 supports this relational interpretation, envisioning a future when “the Lord shall be King over all the earth. In that day it shall be—‘The Lord is one,’ and His name one.” As Tigay notes, this tells us that what was true of Israel’s relationship with Yahweh will eventually extend to all humanity—not that other spirit beings will cease to exist but that Yahweh’s authority will be universally acknowledged.

The Hebrew Scriptures themselves challenge simple monotheistic interpretations through their use of elohim, a plural noun referring both to foreign gods and to Yahweh, the God of Israel. By examining how elohim appears throughout the Hebrew Bible, we find references to spirit beings that are clearly more than mere idols of wood and stone (see Deuteronomy 32:17; Psalm 86:8; 136:2).

The Ten Commandments provide a telling example: “You shall have no other gods before Me” (Exodus 20:3). This commandment presupposes the existence of other gods while requiring loyalty to Yahweh alone. Rather than denying the existence of other divine beings, it establishes a hierarchy.

Other passages support this. For example, in Isaiah 43:10, Yahweh declares, “No god was formed before me, and none will outlive me” (NET Bible). Again, this indicates not the nonexistence of other gods but rather their status as created beings and their ultimate subordination to Yahweh.

Nathan MacDonald, in his work “One God or One Lord? Deuteronomy and the Meaning of ‘Monotheism,’” offers a crucial insight: In Deuteronomy, “the recognition of YHWH’s oneness is a call to love YHWH”—a summons to a relationship expressed through “obedience and worship.” He observes that “the demand to show exclusive loyalty to YHWH depends, for its rhetorical effectiveness, on a common recognition that other gods exist and represent a serious challenge to Israel’s commitment to YHWH.”

This understanding reframes monotheism from a metaphysical claim about numerical divine unity to a practical demand for undivided religious loyalty. The primary concern becomes not whether other spirit beings existed but whether they were worshiped, when Yahweh alone was to be worshiped.

A Fuller Biblical Picture

While Yahweh was to be ancient Israel’s only God, the New Testament shows that their understanding was incomplete. But the biblical texts also present a picture that differs significantly from later Trinitarian formulations.

We can gain an important insight when we consider the apostle John’s statement that Christ “has made God [the Father] known” (John 1:18, NET). If Christ revealed the Father to humanity, this implies that the Father was previously unknown—yet Yahweh was certainly known to the Israelites throughout their history.

This leads us to a remarkable conclusion: Christ Himself must be Yahweh, the God of the Hebrew Scriptures. Such an identification makes perfect sense when we consider that John declares Christ as the one through whom “all things were made” (John 1:3, English Standard Version), which aligns with the Hebrew Scriptures’ presentation of Yahweh as Creator. Moses’ words to Israel—“The Lord [Yahweh] Himself is God in heaven above and on the earth beneath; there is no other” (Deuteronomy 4:39)—would thus refer to Christ in His preincarnate state.

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made.”

The divine hierarchy that emerges from this understanding shows the Father as the supreme, previously unknown God whom Christ came to reveal, with Christ (as Yahweh) serving under the Father’s authority while ruling over all created spirit beings, rather than the later theological construct of three coequal persons within a triune godhead. This explains Christ’s statement that “the Father is greater than I” (John 14:28, ESV)—not because they don’t share divine essence (they do), but because the Father holds supreme authority over even Yahweh/Christ.

Toward a Biblical Understanding

Rather than impose later theological frameworks onto the biblical texts, these observations suggest we should understand divine unity as the biblical authors presented it. The Bible points toward a worldview that acknowledges multiple spirit beings while maintaining Yahweh’s unique status as the uncreated God who rules over all other divine entities.

The traditional numerical definition of monotheism proves inadequate for understanding how the Bible’s authors understood divine reality. Rather than the later theological construct of the Trinity, the Bible presents a clear hierarchy: the Father as supreme God, previously unknown until revealed by Christ, and Christ Himself as Yahweh of the Hebrew Scriptures, serving under the Father while ruling over all created spirit and physical beings.

This biblical understanding illuminates why Christ could simultaneously be worshiped as God (as Yahweh) while acknowledging the Father’s superior authority. The Israelites’ exclusive devotion to Yahweh was actually devotion to the preincarnate Christ, who came to the earth to reveal the previously unknown Father and establish the proper divine hierarchy.

This framework doesn’t diminish the significance of monotheistic faith; rather, it reveals what the Bible’s writers actually presented. The call to worship Yahweh alone in the Hebrew Scriptures becomes worship of Christ in His role as Creator and Ruler, while Christ’s mission reveals the ultimate authority of the Father. In this light, biblical monotheism emerges not as mathematical singularity or later Trinitarian coequality, but as recognition of the proper divine hierarchy with the Father supreme, Christ as Yahweh serving under Him, and all other spirit and physical beings subordinate to both.