Polycrates: Unity or Truth

The fact that the early Church, based in Jerusalem, strove to adhere to the teachings of Jesus Christ may seem self-evident. Also obvious, perhaps, is that the original apostles were considered an authoritative source of those teachings. But that didn’t remain the case for very long as the Church spread beyond its earliest geographical confines.

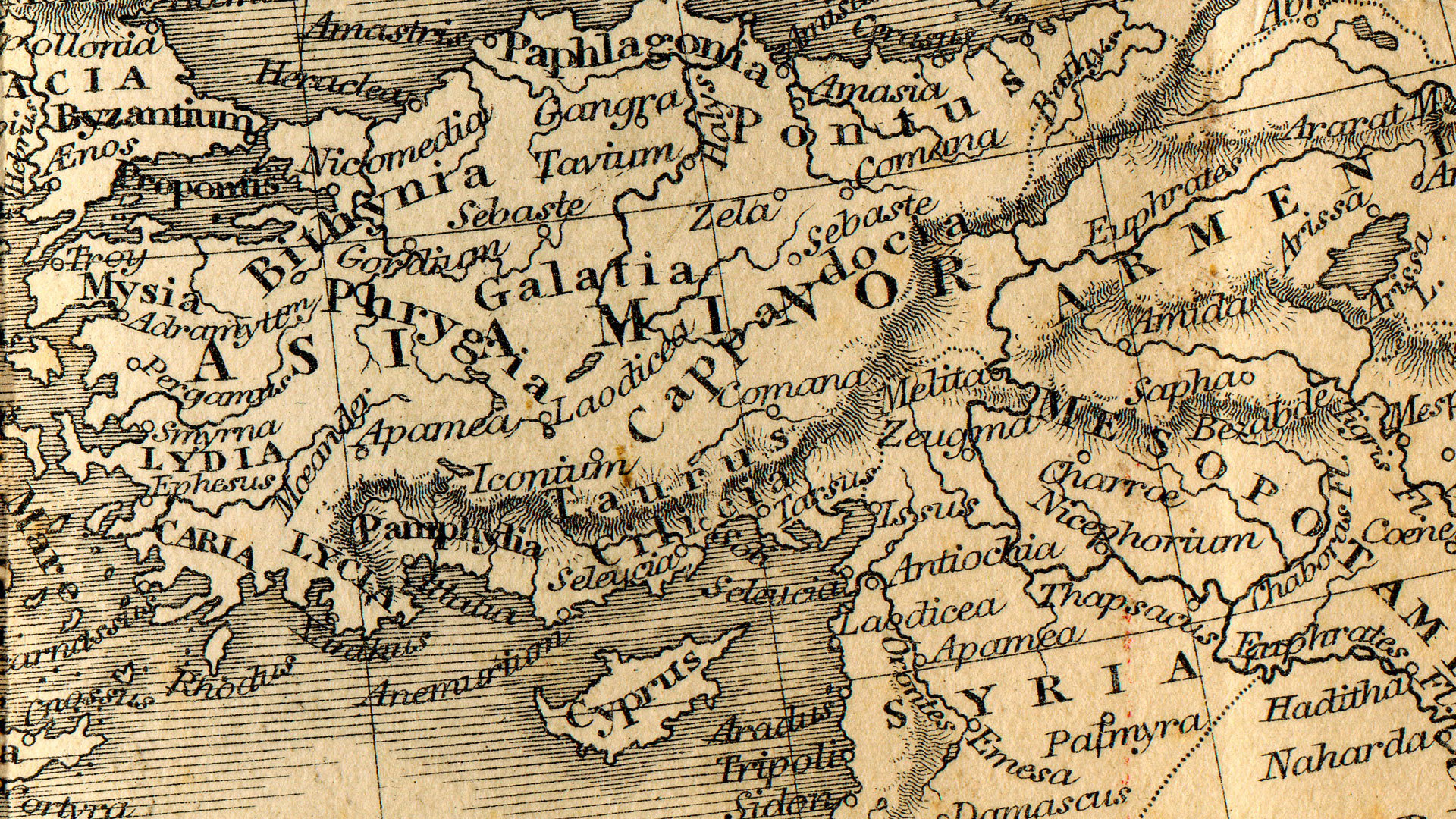

When Jerusalem fell to the Romans in 70 C.E., the Church turned its focus to Asia Minor. Not only had the apostle Paul been active in this area, his assistants there had continued to minister to the followers of Jesus. The apostle John reportedly settled in Ephesus, the principal Roman city of the area, and the Apocalypse written by him contains letters to seven of the churches in Asia Minor.

This is where we find the Church leader Polycrates as the second century comes to a close. He was the successor of Polycarp, a disciple of John, and his family had been a part of the early community of believers. They had faithfully preserved the apostolic teachings from the first century. By his time, however, church groups in other parts of the world had accepted doctrines that were contrary to apostolic teachings.

Around 190, Polycrates found himself under pressure from Victor, bishop of Rome, to compromise his beliefs about the New Testament Passover and to accept new practices. The new ideas would later become the basis of Easter celebrations. Polycrates faced a choice: Would he compromise on a point of truth that had been handed down from the apostle John or accept Victor’s nonbiblical teachings?

Eusebius, in his Ecclesiastical History (5.24), describes the outcome of the controversy: “But the bishops of Asia, led by Polycrates, decided to hold to the old custom handed down to them.” Eusebius quotes Polycrates, who insisted, “We observe the exact day; neither adding, nor taking away.” Polycrates continued, naming Philip, John and Polycarp among the faithful apostles and forefathers: “All these observed the fourteenth day of the passover according to the Gospel, deviating in no respect, but following the rule of faith. And I also, Polycrates, the least of you all, do according to the tradition of my relatives, some of whom I have closely followed. For seven of my relatives were bishops; and I am the eighth. And my relatives always observed the day when the people put away the leaven. I, therefore, brethren, who have lived sixty-five years in the Lord, and have met with the brethren throughout the world, and have gone through every Holy Scripture, am not affrighted by terrifying words.”

Victor reacted to this bold and confident statement by attempting to excommunicate all of the churches in Asia Minor. Several other church leaders, however, were appalled by this severe and heavy-handed action against those whose only crime was to remain faithful to the beliefs and practices of the early Church. Eusebius writes that it “did not please all the bishops. And they besought him to consider the things of peace, and of neighborly unity and love. Words of theirs are extant, sharply rebuking Victor. Among them was Irenaeus, who . . . admonishes Victor that he should not cut off whole churches of God which observed the tradition of an ancient custom.”

A generation earlier, Polycarp and Anicetus, who was then the bishop of Rome, had discussed this same controversy. At that time each man considered the other to be of equal rank or status. When they failed to agree over the issue, each held to his own view but they remained on friendly terms. That was not to be the case this time, however: Victor’s resolve remained firm.

“We ought to obey God rather than men.”

While there is no record indicating whether Polycrates eventually died a martyr, it is clear that he was not afraid to hold fast to his beliefs in the face of Victor’s intimidation and threats. He comes across as a humble man who had respect for those in positions of authority, but who did not consider preservation of unity within the church a valid reason to compromise on matters of belief and practice that had been handed down to him from Jesus Christ through the apostles. His response to Victor’s threats is a summation of his legacy and echoes the apostles’ words in Acts 5:29: “We ought to obey God rather than men.”