Job’s Comfort

Understanding God in Times of Suffering

The book of Job offers insight into human suffering, as well as a valuable lesson we can take from it.

LIRE LE PRÉCÉDENT

(PARTIE 32)

ALLER À LA SÉRIE

The book of Job is unlike any other in the Bible. It’s claimed that apart from the book of Psalms, more literature has been written about Job than any other Bible text. Job is one of Scripture’s wisdom books, which, along with Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, are part of the division known as the Writings.

Though a very old book, written perhaps around the time of Abraham (two millennia before Christ), it says nothing about Job’s origins. In scant detail, we learn that he “was blameless and upright, and one who feared God and shunned evil,” that he came from the otherwise unknown land of Uz, and that in terms of wealth he was “the greatest of all the people of the East” (1:1, 3). It’s as if the usual personal details of a narrative are deliberately set aside, so that we are forced to focus on the massively important main theme: What are we to do when we undergo suffering, and how are we to understand God’s role? These seem the more important questions, rather than the familiar puzzle as to why a good God allows good people to suffer. Often thought to be the emphasis in the book, no direct answer to this question is given. But various truths about how to suffer do emerge from the heart of the book, as Job and his four friends present their cases and God replies.

The patient Job on view in the opening chapters is a wonderful example of calmness and composure under intense difficulties; but equally the impatient, bitter, and angry Job of most subsequent chapters teaches us that only by acknowledging God’s wisdom and sovereignty in suffering can we achieve equanimity once more. The book is more about God’s policies and less about Job.

“Job is the test case for considering how God runs the world and how we should think about God when life goes haywire.”

The organization of the book may be understood as comprising three sections. By one reckoning, these include the narrator’s opening and closing (chapters 1 and 2; 42:7–17), and a core in the form of poetic speeches (3:1–42:6).

Another structural view of the book also maintains three sections. Within the first section Job is presented, as before, as a wealthy family man whose godly obedience and character is allowed by God to be put to the test by the Adversary, Satan, who claims that Job only follows God for his own benefit: “Stretch out Your hand and touch all that he has, and he will surely curse You to Your face!” (1:11).

God allows Satan to ruin Job, knowing that Job’s righteousness will sustain him. But this conclusion—that despite being reduced to practically nothing, devastated by the sudden loss of health, wealth, family, status and reputation, Job will remain faithful (1:12–2:10)—is about to be probed deeply as the sufferer’s innermost feelings begin to surface. Within a matter of days, Job “opened his mouth and cursed the day of his birth” (3:1).

In the second section, we hear Job and three of his friends—Eliphaz, Bildad and Zophar—debate the cause of his tragic condition across 28 chapters, in which Job even issues a legal challenge to God for unjust punishment. This section continues until “the words of Job are ended” (31:40).

The third section begins with a fourth friend, Elihu, offering more advice (chapters 32–37) that Job is not allowed to answer, until God Himself intervenes (38–41) with questions that Job cannot answer. Then, in true humility, Job finally recognizes his error, admitting that God alone is supreme, the source of all wisdom, and not answerable to man. At last he finds his true “location” in life. This leads to God blessing him more than before and to his years being extended (42:10, 12–17).

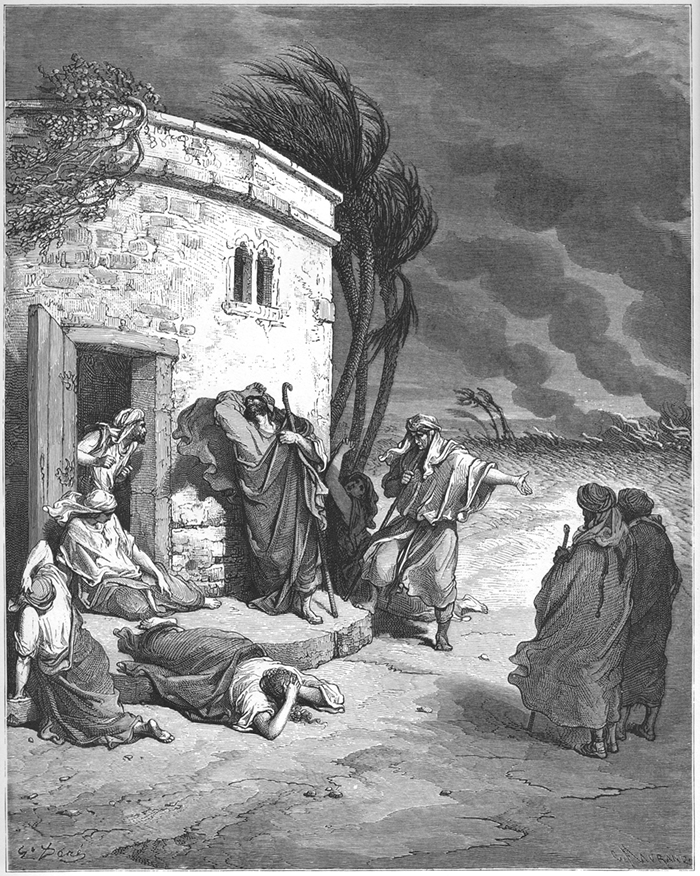

Job Hearing of His Ruin by Gustave Doré, engraving (1866)

Job’s Quandary

At root, the book of Job explores ideas about the moral order of human life. It’s a debate that echoes down to our time. Even today there is the assumption that prosperity results from good deeds and that suffering is the result of sin. This is known as the doctrine of retribution, or the just-world hypothesis. Job’s three friends are sure that their previously righteous and blessed colleague must be suffering as the result of sin. While they vary in their application of this belief, they all conclude that Job is suffering because either he or his children have sinned in some way, even trivially or secretly. But as Job points out, that isn’t the case; he has done nothing wrong.

“The order of creation sets the standard for the moral order of the universe; and that is, that God must be allowed to know what he is doing, and lies under no obligation to give any account of himself.”

The fourth friend, Elihu, is a younger man and at first reluctant to speak before his elders. But he eventually realizes that youth is not necessarily a barrier to speaking wisdom. His view is that, rather than suffering being the result of a cold, inexorable, mechanistic process, allowing suffering is one of the ways God reaches out to us. But again, this attempt to refine the idea of retribution does not fully answer Job’s situation.

Throughout the book, Job attempts to reason his way out of the dilemma of why he is suffering when he has done no wrong.

At first he tries to accept the losses he has suffered: “Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return there. The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord” (1:21).

Soon, however, overcome by the destruction of the order he has always enjoyed, he wishes he had never been born: “Why did I not die at birth? Why did I not perish when I came from the womb?” (3:11). In growing despair, he wishes that God would kill him: “Oh . . . that it would please God to crush me, that He would loose His hand and cut me off!” (6:8–9), because there is no point in living. “I loathe my life; I would not live forever” (7:16).

Before long he decides that the God he obeys must answer him in a metaphorical court of law: “I desire to speak to the Almighty and to argue my case with God. . . . Though He slay me, yet will I hope in Him; I will surely defend my ways to his face.” Then, addressing God directly, he says, “Summon me and I will answer, or let me speak, and you reply to me. How many wrongs and sins have I committed? Show me my offense and my sin” (13:3, 15, 22–23, New International Version).

In all this Job does not lose his belief in the plan God has for humanity. He knows that after his death he will live again by resurrection, following God’s appearance on the earth: “For I know that my Redeemer lives, and He shall stand at last on the earth; and after my skin is destroyed, this I know, that in my flesh I shall see God” (19:25–26).

God’s Sovereignty

Before Elihu, who has been quiet to this point, presents his own assessment of the situation (chapters 32–37), Job makes his final speech, declaring his innocence once more (29–31). But this time he insists on signing a declaration to that effect: “O that I had one to hear me! (Here is my signature! Let the Almighty answer me!) O that I had the indictment written by my adversary!” (31:35, New Revised Standard Version). If Job is correct and his suffering is not the result of sin, then there is no truth in the doctrine of retribution.

But now comes the moment for God’s intervention and answer (38–41). God’s speeches never mention retribution. They are neither for nor against the idea. Instead, God questions Job from three perspectives, each helping him see his insignificance in the grand scheme of life.

“God invites Job to reconsider the mystery and complexity—and the often sheer unfathomableness—of the world that God has created.”

First, Job is asked about his lack of participation in the creation of the earth: “Where were you when I laid the foundations of the earth? Tell Me, if you have understanding” (38:4). Of course, he has no answer. Then there are the mysterious workings of the world: “Have you entered the springs of the sea? Or have you walked in search of the depths?” “By what way is light diffused, or the east wind scattered over the earth?” (38:16, 24). And there are the ways of wild nature to ponder: “Can you hunt the prey for the lion . . . ?” “Can you bind the wild ox in the furrow with ropes?” “Does the hawk fly by your wisdom . . . ?” (38:39; 39:10, 26).

Job cannot explain how the physical world is managed, nor the purpose of great wild creatures such as Behemoth and Leviathan (40:15; 41:1; many consider these to be the hippopotamus and perhaps the crocodile, with some features exaggerated for effect). God alone knows such things.

In a similar way, man cannot know why God sometimes allows suffering for no apparent reason. There are limits to human understanding of God’s created world. This neither supports nor denies the doctrine of retribution; it sets it on one side in Job’s case. Man must come to see God as sovereign over His creation—including humanity—the one Being who need not account for Himself to mankind.

When Job is ready to accept this reality, he has come to a deep understanding of his place in the creation: “You asked, ‘Who is this who hides counsel without knowledge?’ Therefore I have uttered what I did not understand, things too wonderful for me, which I did not know” (42:3). Job is no longer dislocated from nature and the Creator but has found, and is restored to, his place: “I have heard of You by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees You. Therefore I abhor myself, and repent in dust and ashes” (42:5–6).

The book concludes with the narrator’s voice explaining that Job’s three friends were indeed at fault. Quoting God’s words to Eliphaz, he writes, “My wrath is aroused against you and your two friends, for you have not spoken of Me what is right, as My servant Job has” (42:7).

Here is confirmation that what Job had spoken about his suffering was correct. They knew nothing of Satan’s role. It was not a punishment, but neither can we know in every case the reason for suffering.

It was only by offering a sacrifice and by Job praying for them that the three “comforters” could be accepted again. With this accomplished, Job’s fortunes were restored and his blessings multiplied, demonstrating that the doctrine of retribution still applies, but according to God’s sovereign choice in individual cases. “So Job died, old and full of days” (42:9–17).

Ultimately, Job’s comfort came from God, not from man.

LIRE LE PROCHAIN

(PARTIE 34)