The Magdalene Gospel

What Do We Really Know About Mary Magdalene?

The Bible offers few details about her. Yet Mary Magdalene is a larger-than-life figure in non-biblical texts. What can we know about her and her historical significance?

Among the many women whose stories appear in the Bible, one in particular has gained a great deal of attention in recent years. She is one of the most mentioned female disciples of Jesus, appearing in each of the four Gospels. Catholicism refers to her as Saint Mary Magdalene, having also identified her as both an apostle and a sinner. And apocryphal texts such as the Gospel of Mary contain intriguing speculations about her life and role in the early Church.

Theologian Meggan Watterson highlights the Gospel of Mary as a source of new knowledge and religious practice in her book Mary Magdalene Revealed: The First Apostle, Her Feminist Gospel and the Christianity We Haven’t Tried Yet. Watterson’s website describes the Gospel of Mary as being “as ancient and authentic as any of the gospels that the Christian bible contains.” It goes on to say that it “was buried deep in the Egyptian desert after an edict was sent out in the 4th century to have all copies of it destroyed. Fortunately, some rebel monks were wise enough to refuse—and thanks to their disobedience and spiritual bravery, we have several manuscripts of the only gospel that was written in the name of a woman: The Gospel of Mary Magdalene.”

This is intriguing, but are this gospel and its story reliable? Who is the book’s namesake, and what can we know about her for certain?

Let’s consider first what the Bible says about Mary Magdalene, and then look at how that account differs from other sources.

Who She Was

The term Magdalene suggests Mary’s place of origin, which is understood to be Magdala, a town located on the western side of the Sea of Galilee between Cana and Nazareth. The Bible indicates that Jesus traveled several times through this area in His early life and ministry, spreading His message and finding an attentive audience of followers who believed His words.

One of the earliest references to Mary is in the book of Luke, where she is listed among the community of believers: “Soon afterward he went on through cities and villages, proclaiming and bringing the good news of the kingdom of God. And the twelve were with him, and also some women who had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary, called Magdalene, from whom seven demons had gone out, and Joanna, the wife of Chuza, Herod’s household manager, and Susanna, and many others, who provided for them out of their means” (Luke 8:1–3).

Though the Bible says Mary had been healed of demonic influence, it doesn’t elaborate on her former condition as it doesn’t seem to be relevant to the rest of her story. The account doesn’t say specifically that Jesus was the one who healed her, but her previous problems are resolved and she appears to have become a follower of Jesus from that point.

“Mary Magdalene is the only major character in the New Testament out of whom, it was said, demons had been exorcised. That said, this is the only mention of Mary Magdalene in the gospels prior to the crucifixion of Jesus.”

This passage in Luke’s Gospel also suggests that Mary was a woman of means who financially supported Jesus’ work. Later examples demonstrate that this was a common practice. Women such as Lydia, mentioned in Acts 16, supported the first-century followers of Jesus in this way.

All other scriptural references to Mary are found in the accounts of Jesus’ final hours. At the scene of the crucifixion, it appears that many disciples had abandoned their teacher, but Mary and other female followers were present, “looking on from a distance” as Jesus died (Matthew 27:55–56; Mark 15:40–41).

Mary Magdalene, as one of those who stayed nearby through these events, waited, watched, and noted where Jesus was buried (Mark 15:47). The biblical account indicates that she and others later brought spices to anoint His body but found the tomb already open (Mark 16:1). Mary was the first to see Jesus after His resurrection, so He instructed her to take the news to the other disciples (John 20:10–18).

Eventually Jesus appeared to the rest of the disciples in various contexts, and also to many others (1 Corinthians 15:3–8). The Bible simply lists Mary as one among these many witnesses, albeit the one who took the initial message back to the group of fearful disciples.

But with the conclusion of the Gospel accounts, Mary’s story also ends.

Who She Was Not

While her biblical story is uncomplicated, there are some common misunderstandings about Mary Magdalene.

One persistent idea is that she was a former prostitute. Luke 7 describes a sinful woman who anointed Jesus’ feet and was forgiven. However, this woman isn’t named, and there is no indication in the Bible that she was Mary Magdalene.

A similar event in John 12 contributes to the confusion. Among Jesus’ followers were a man named Lazarus and his two sisters, Mary and Martha. This Mary performed a similar anointing, so her identity has been conflated with that of the unnamed woman from Luke. Multiple stories have been merged into one, creating a composite figure commonly identified as Mary Magdalene.

This confusion was unfortunately formalized in 591 CE, when Pope Gregory I wrote a homily identifying Mary Magdalene as the sinful woman of Luke 7 and explicitly naming that sin as sexual—a detail not expressed in the biblical narrative. This view appears to be based more in Roman Catholic dogma than in a close reading of the text. Despite the fact that in 1969 the Roman Catholic Church quietly recanted that teaching, the idea persists.

Another idea put forward in recent years has added to the legend surrounding Mary. Some have posited that Jesus had a physical relationship with her, a theory picked up by popular culture in novels and such movies as The Last Temptation of Christ. As the idea developed further, Mary became the “holy grail” of legend, suggesting that she and Jesus had children together, and that His bloodline included the Merovingian French kings.

The idea of a physical relationship is bolstered by a line in the gnostic Gospel of Philip. Discovered in 1945 in a collection of codices at Nag Hammadi in Egypt, this apocryphal work tantalizingly states that “[the Lord loved Mary] more than [all] the disciples, and kissed her on her [mouth] often. The others too . . . they said to him ‘Why do you love her more than all of us?”

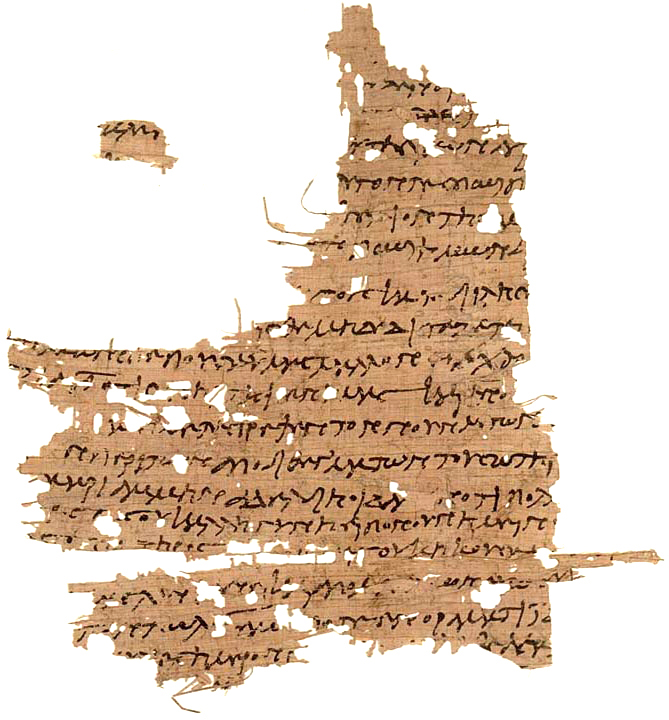

A fragment of the Gospel of Mary, showing lacunae of various sizes where the papyrus has decomposed over the centuries. When paleographers attempt to fill in the missing text, they must sometimes guess at what was once written there.

This text is difficult to decipher, however, because the original pages are damaged. Lacunae, or holes in the ancient papyrus, result in gaps in the text. Sections indicated by ellipses are too lengthy to make a suggestion as to the missing words. In the example above, the ellipsis therefore results in an incomplete sentence. To come up with the bracketed words to fill in smaller lacunae, paleographers rely on clues from other sections of the document or comparable texts from the period in which the document was written. But these words are guesses. So rather than mouth, the missing word could just as easily be hand, cheek, forehead or feet; thus, other commentators simply leave it as an unknown.

“The author of the Gospel of Philip is not trying to suggest that Jesus and Mary were lovers. He only wants to elevate Mary to the level, or even beyond the level, of the other disciples.”

Can we conclude that this text is evidence of a non-platonic relationship, or even a marriage? During the time of the Gospel writers, a kiss was a standard form of greeting and need not have any sexual connotation. The apostle Paul, for example, closed his second letter to the Corinthians by telling them to “greet one another with a holy kiss” (2 Corinthians 13:12).

This same form of greeting shows up in several other books in the New Testament, including the book of Matthew, where Judas greets and betrays Jesus with a kiss. Tantalizing as the idea may be, there is no evidence of this greeting indicating a physical or marital relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene.

Gnostic Ideas from the Second Century

The Gospel of Mary was first discovered as a part of the Berlin Codex in the late 19th century in Egypt. Only six of the work’s 19 pages were found. Two other fragments were discovered a few decades later, and a translation was first published in 1955.

Esther A. de Boer, who was a professor in New Testament at the Protestant Theological University in Kampen, Netherlands, wrote several books about the Gospel of Mary. In The Gospel of Mary: Beyond a Gnostic and a Biblical Mary Magdalene, she stated that this apocryphal gospel “is clearly different from the Gospels in the New Testament. Whereas the New Testament Gospels describe the work of Jesus in his earthly lifetime, the Gospel of Mary describes a post-resurrection dialogue which is rather philosophical.”

In other words, this gospel relates discussions between the disciples and Mary that occur after the resurrection. Peter asks Mary to tell him what secret knowledge Jesus gave her; then there is one of several gaps in the manuscript, after which she describes the soul ascending up through the heavenly realms under control of various evil forces.

According to de Boer, the New Testament does record such discussions between Jesus and the disciples after the resurrection, but “they are not about notions such as matter and nature, let alone about the origin of a vision, the relation between soul, spirit and mind, and the dangers the soul has to conquer on its way to the eternal Rest.” The Gospels and Acts describe these conversations as more practical, with Jesus’ followers wanting to know how life would change for them: What events should they expect next? What new understanding would Christ bring to the Scriptures? What should the disciples plan to do going forward?

Secret Knowledge

Much of the material in these apocryphal works is understood to come out of a different philosophical tradition—one that developed alongside first-century Judaism and the early New Testament Church.

Gnosticism was a set of ideas and syncretistic beliefs focusing on secret knowledge, or gnosis in Greek. Taking hold among some second-century Christians, it held that the human body was corrupt but the human spirit was naturally good. Freeing the soul from its physical prison was therefore the real focus in the quest for salvation; and releasing the soul required access to mysterious knowledge that only the Gnostics possessed.

“There were boundaries of belief and behavior even in the first century, boundaries beyond which Jesus’s followers knew they should not go; and the Gnostic documents clearly crossed these boundaries in various ways.”

Some Gnostics deny that Jesus had a real physical body (as that would be evil), and therefore His humanness and His resurrection were illusions. Others say that He did have a physical body, but that it was separate from His spirit so that the body He inhabited did suffer and die, but the spirit never suffered.

The apostle Paul and other Bible writers actively combatted gnostic ideas that were already developing in the first century, as well as others that were contrary to Jesus’ teachings. Paul warned the early Church: “See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ” (Colossians 2:8).

The Risks of Speculation

New Testament scholar Ben Witherington III explains that “though it may be fashionable to suggest that we should be gracious and include the Gnostic texts along with the New Testament as equally valid sources of the truth about early Christianity, the truth is that both sources cannot be correct about the historical Jesus, or about the nature of the movement he set in motion, or about the people he consorted with, such as Mary Magdalene.”

In other words, gnostic writings including the gospels of Philip and Mary were excluded from the Bible for a reason: not only are they later works, but they present contradictory ideas that aren’t compatible with who Jesus was and what He taught.

Another early New Testament writer encouraged the followers of Jesus that when things got difficult, they had a reliable source to turn to without needing to rely on secret knowledge or philosophy: “You, however, must continue in the things you have learned and are confident about. You know who taught you and how from infancy you have known the holy writings, which are able to give you wisdom for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus. Every scripture is inspired by God and useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the person dedicated to God may be capable and equipped for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:14–17, New English Translation).

It surely must be exciting to stumble across a previously unseen document, a piece of history that seems to tell a different version than the one we know. A new truth, a new interpretation, a new idea—it can be intriguing. It can challenge previous beliefs, perhaps open up new ways of seeing and contextualizing what we understand. But while it’s important to be open to the correcting of wrong ideas, caution is warranted when contradictions appear, and when missing information or personal biases give rise to speculation or unwarranted conclusions.

In the field of Bible scholarship, when a newly discovered document, fragment or idea doesn’t agree with a close reading of the biblical text, it’s worthwhile to examine it critically. Speculation and filling in gaps based on our own views, traditions or philosophies can easily lead to confusion and error.